Lunga ed interessante prima parte.

Bruce Frederick Joseph Springsteen was born in Freehold, New Jersey, September 23, 1949, the firstborn of Douglas and Adele Springsteen, who would go on to have two other children, Virginia, a year younger than Bruce, and Pamela, thirteen years his junior. The name Springsteen is Dutch, although Douglas Springsteen is solid Irish and Adele, Italian. Contrary to popular belief, there is no Jewish blood in the mix, commonly thought to be so due to the family’s surname.

Both Bruce’s parents were, in fact, Catholic. Springsteen attended St. Rose of Lima Catholic grade school. It’s likely most of the stories about his run-ins with the nuns, either being slapped by them or by other students at their instructions, are true. What is perhaps more important are the abstract rewards Catholicism gave to Springsteen’s nascent artistic personality that would one day find expression in a lyrical form based on the confessional.

The early shyness that led to Bruce’s self-imposed isolation as a youngster was likely due, at least in part, to his father’s inability to hold a steady job. The family was therefore forced to move around the perimeter of central New Jersey, in and out of Asbury Park, Neptune, Atlantic Highlands, and Freehold (where Douglas Springsteen had spent much of his childhood).

Springsteen appears to have been something of a loner, rarely playing (or allowed to play) with other children, a small boy subject to the tight reins of a strict Euro-American Catholic upbringing. His early rebellion against it took form in the outlets most accessible to the boys of his generation—movies, TV, and rock and roll. Elvis was his primary creative influence, first on the radio, then, when Bruce was seven, in performance on “The Ed Sullivan Show.”

Charged by the potent Presley image, Bruce began, at the age of nine, to experiment with a guitar his mother bought him, his first attempt at forming an identity separate from the family. Springsteen’s initial failure to playthe guitar has often been explained by something he once said in an interview about his hands being too small to master the neck of the guitar. More likely, Bruce’s inability was the result of an early, instinctive conflict between the struggle to succeed and break free from his father’s image and the desire to fail and by doing so pledge allegiance to his old man. It’s not uncommon for young boys to experience a version of this interior battle. Most of the time, the conflict is resolved by the supportive behaviour of the father.

By the time Bruce entered high school, three significant events had occurred in his life. One was his discovery of Elvis; one was attending Freehold Regional High School, a public school rather than Catholic (probably due to his father’s inability to pay for private school, and not, as has often been reported, because of his ability to convince his parents he’d had enough of Catholic school); and one was The Beatles’ appearances on “The Ed Sullivan Show.” When asked what renewed his interest in the guitar after he’d given it up the first time, Bruce responded, “TV . . . The Beatles were out at the time. Seeing them on TV.” By now, Bruce’s troubles with his father had intensified, as had his love of rock music. The Beatles may have symbolised to him as much an emotional liberation as a musical revolution.

Although Springsteen recalled in an interview years later that he’d purchased his first guitar, used, at a pawn shop and having done so had “found the key to the highway,” the moment was captured in an infinitely more revealing, highly dramatic lyrical fashion (that actually combined the facts of the acquisitions of Bruce’s first and second guitars) as part of an untitled song he performed only once in public and never officially released on record.* In it, a little boy recalls he received his first guitar after he and his mother walked in the cold, dirty city- sidewalk snow to a used-musical-instrument store to stare at a used guitar in the window; the same one he was to find under the family Christmas tree. The song, more so than any interview Bruce ever gave, linked the emergence of his creative side directly to his feelings for his mother, the “star on top of the Christmas tree” symbolising both Bruce’s love for his mother and his dream that, as a result of her gift, his own star would rise. The next verse pictured a young Bruce lying in bed listening to the sounds his mother made as she dressed for work, followed by memories of the women at his mother’s office, the sound of their silk stockings and rustling skirts the aural accompaniment to this vividly Oedipal preadolescent imagery. And following that, a verse distantly focused on his father’s “deadly world,” and how it was Bruce’s mother who saved him from following his father’s footsteps into it. A verse or two later, the song flipped to a teenage Bruce who’d brought his hot rod around for his mother to see, and in a scene anticipating the nights he’d dance with his mother onstage during the Born in the USA tour, the boy in the song promised to find a rock and roll bar where he could take his mother out dancing.

Bruce became obsessed with learning how to play his new instrument. Everything else took a backseat—school, girls, cars.

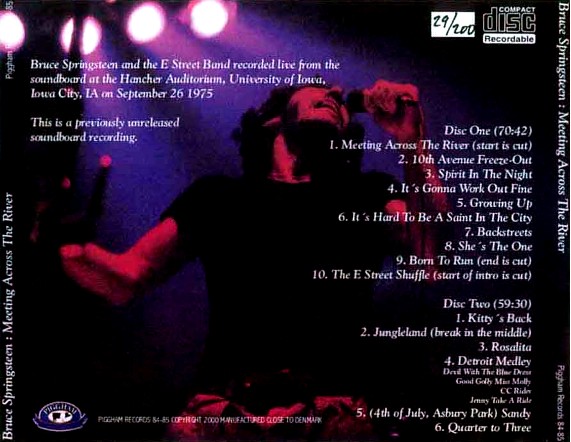

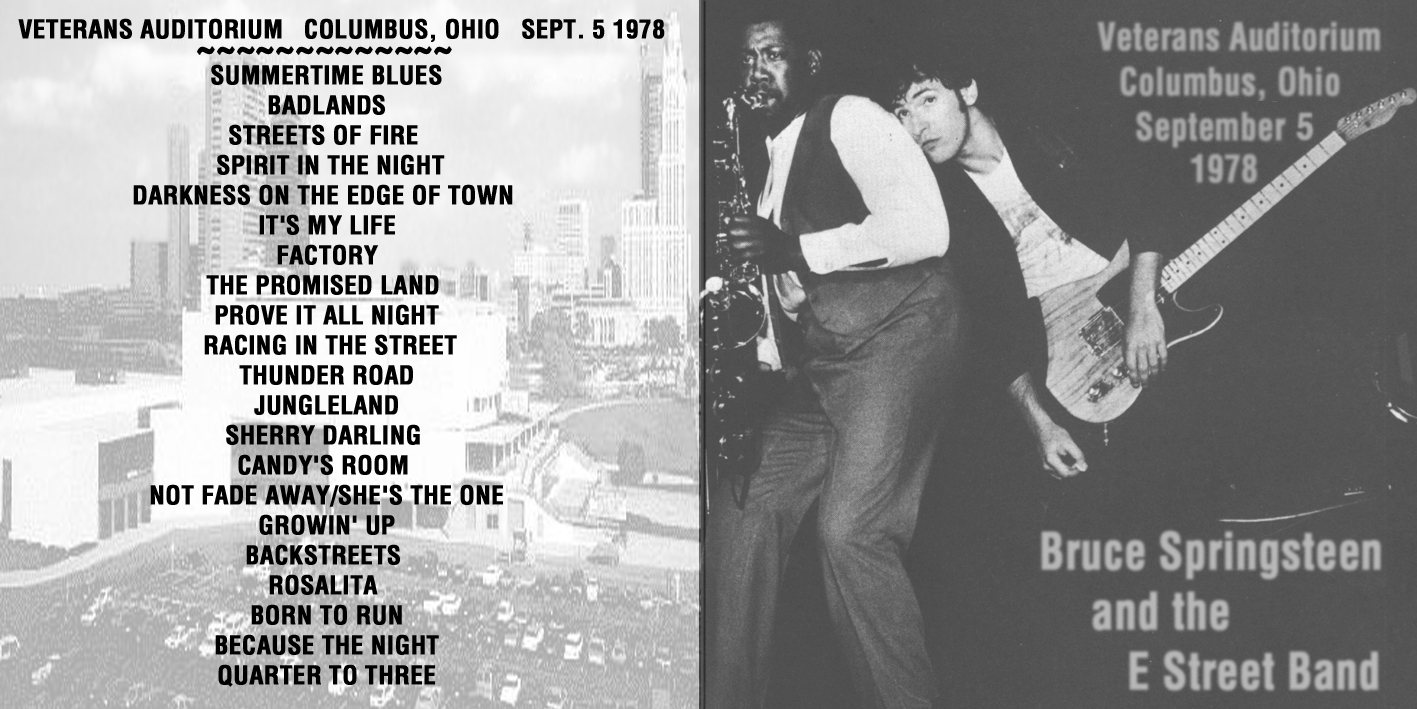

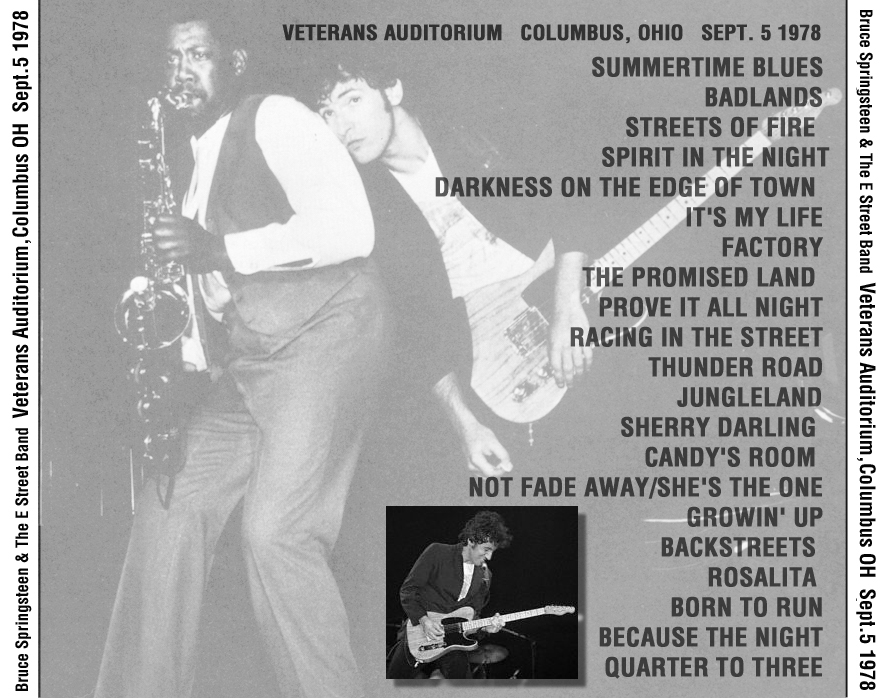

* The only known performance of this unnamed song was November 17, 1990, at the benefit for the Christic Institute, where Bruce performed an extended solo set. Bootleg tapes and CDs of that performance are available in the rock and roll commercial “underground,” as are most of Bruce’s live performances illegally recorded throughout his entire career. Because of his relatively few “official” releases, and his reputation as one of rock’s great “live” performers, Springsteen bootlegs are among the most wanted, and highest priced.

Even his love of sports (due at least in part to his diminutive size) paled against the immediate, solo surge of conquest he experienced through his music. Still extremely shy, with a face ravaged by acne, Bruce avoided the majority of other students at school, preferring instead to hang with the potheads, acid freaks, and leather- jacketeers, all of whom had one thing in common, a growing obsession with rock and roll.

One schoolmate recalled how Bruce used to have these fights with his father that, the schoolmate believed, occasionally turned physical. “I’m sure to escape, he stayed mostly alone and lost himself in music.”

SPRINGSTEEN: When I was a kid, I really understood about failure; in my family you lived deep in its shadow. I didn’t like school. I didn’t like people. I didn’t like my parents…. The radio in the fifties for me was miraculous. It was like TNT coming out of those speakers. It came in and grabbed you by the heart and lifted you up. “Under the Boardwalk, ” “Saturday Night at the Movies ” *—those things made me feel real. Those songs said that life

was worth living. . . the radio—rock and roll—went where no other things were allowed to go.

Although Bruce was hardly an A student, he was a reader. Sinclair Lewis’s muckraking novel of the injustices of working class life, The Jungle, made a particularly strong impression on him. Undoubtedly, the book’s tough- toned narrative spoke to him in a way few other high school texts did, and stayed with him. Its naturalistic language and social themes reverberate throughout Springsteen’s stylistic as well as thematic approach to lyric writing.

By the time Bruce graduated from high school, he was already a veteran of the band life. The usual tales of Bruce’s joining The Castiles are fraught with all kind of “cutesy” stories wherein Tex Vinyard is described as some cartoonish character straight out of Walt Disney, a local promoter who first guided Bruce into the world of high school rock bands. Vinyard was a character on the local music scene who often became involved with young bands. He first heard of Bruce through the local music grapevine.

In fact, The Castiles wasn’t even the first band Bruce played in. *Correct title is “Another Saturday Night.”

SPRINGSTEEN: I was thirteen and a half. . . when I started working. [I played] the guitar, I started around when I was thirteen, I guess. Practised for about six months and started playing in a band. I worked at The Elks Club and you know, for free. Just went down there and played. The guy charged fifty cents for kids to get in. I had a small band [The Rogues, a group he ‘d joined, in which he was neither the group ‘s leader nor lead singer]. I don’t remember the names [of the other members]. Let me see. [We did The] Elks Club. Some other clubs, you know, high school dances. The usual stuff. We were too young to play the bars. We did benefits, like hospitals, you know, different things, you know. If you were making fifty dollars, you were making a lot of money, I guess, for a night’s work.

Bruce played with The Rogues for about a year, doing, as he recalled, about one show a month. The leader of the band, and the one who booked the actual dates, was the drummer, a boy Bruce only remembered as having the last name Powell. It was only after the breakup of The Rogues that Bruce joined The Castiles . The history of The Castiles is hardly more glamorous than that of The Rogues. Recalled Bruce of his life immediately after graduation:

SPRINGSTEEN: I lived in town with some of the guys from the band. [The rent was] a hundred something, a hundred fifty, something like that. Three of us, I guess [shared the place] on South Street. I was in The Castiles for about three years . . . up through ’67. [We performed for] high school dances, church organizations, church things, CYOs [Catholic Youth Organizations], and down in the [Greenwich] Village . . . The Cafe Wha.

Bruce moved in with his fellow band members after his father had decided to start a new life in California. Still experiencing difficulty making ends meet, the senior Springsteen moved the entire family to San Mateo. Bruce refused to go along, preferring the homeboy security of the Jersey Shore. Out of a sense of longing, perhaps, once the family had left, Bruce moved back into the family’s rented house and lived there _until forcibly evicted. It was at this time he first sought out a series of relationships with older father-figure managers. Here, in Bruce’s words, is how Vinyard came into his life.

SPRINGSTEEN: We had a guy who was sort of manager. Tex Vinyard. He was just a guy, you know. Some guy came over to my house one day and said, “Hey, join my band. ” I went over and met this guy. He was just a local—I think he worked in a factory down there . . . just a guy that was around.

The first booking at The Cafe Wha wasn’t set up by Vinyard. The band’s drummer, also named Tex, was the one who went to the club owner and convinced him to give the band a shot.

S P R I N G S T E E N: [The Castiles were] George Theiss . He s till works. Guy named Skiboots, and he doesn’t work no more. A guy named . . . Bob. Bob Alfano. He works a little bit. I think we made one [recording]. It is a little, like, plastic demo record. Tex brought us to this place, this little studio on Highway 35. We went in and had a half hour or an hour and we did it. One of mine [“That’s What You Get” and “Baby I,” both unreleased]…. It was like … it was funny. It was just to say that you made a record, I guess.

As to how Vinyard came to manage the group, Bruce recalled:

S P R I N G S T E E N: It was the kind of thing, everybody sitting around the kitchen, somebody says, “I will be the manager, ” and somebody says, “It’s a great idea. ” We performed two, three times a week sometimes. I used to get maybe twenty dollars a night. We were advised [by others, not Vinyard, club owners, booking agents] to play Top 40 and dress alike.

The Castiles broke up in the summer of ‘6~ perhaps because they were running in place; but more likely, as Bruce recalled (left out of virtually every other account of the brief history of the band), because “everybody got arrested one night and that was the end of the band…. I think it was the first dope bust there ever was in Freehold. [Afterward] guys went here, guys went there. There was just nothing there anymore.” Bruce was not

directly involved in the bust, but by his account several members of the band may have been. At any rate, the band broke up. (The drummer subsequently enlisted in the army, went to Vietnam, and was killed in action.) Bruce, while searching for a new band, managed to get a solo booking in a small bar in Red Bank, New Jersey.

SPRINGSTEEN: I knew the fellow that was running the place. If nobody was there, I would get up and play. Might have picked up ten or twenty dollars. I played there once a month, maybe once a week. The name of the place was The Off Broadway. This has to be the end of—maybe the beginning of ’68, end of ’67. I was a guitar player. It was like a hootenanny type place. It was a folk place is really what it was. I sang my own songs. [Then] I got in a band called—it was the Steel Mill.

Even Viola, a member of the New Jersey music scene for twenty-five years, recalled how he first heard of Bruce.

KEN VIOLA: The first time I ever saw Bruce Springsteen play was in 1967 when he was in a band called Earth, which was a three-piece band—guitar, bass, and drums—that did covers of songs by Tim Buckley and things of that nature. It was probably down in Monmouth High School. I couldn’t believe there was a band that was covering Tim Buckley. It blew me away. Bruce was singing lead. Shortly after that I started playing in a band and we’d go down and play the Shore circuit, early in ’68, and Bruce at that time was trying to find his way.

Bruce had discovered the music scene in Asbury Park. It was there that Earth began~ and there it ended, rather quickly and rather anonymously. Perhaps the most unforgettable performance was one that took place not on the Jersey Shore, but in the relative exotica of Manhattan.

SPRINGSTEEN: We performed at firemen’s fairs, high schools, [and once in] New York. The Diplomat Hotel. I don’t think there was an occasion at the time. We played in a ballroom. They bused people up from New Jersey. [There were] two thousand people, maybe, in the audience.

For the rest of Earth’s bookings, about a year’s worth of gigs, Bruce averaged fifty dollars a night.

VIOLA: [By] 1969, a club had opened, The Upstage, which was above a Thom McAn ‘s [shoe store] down on Cookman A venue. It was an after-hours club for musicians. You walked up the stairs and there was this little room off to the left that had this office where Tom Potter, the guy who ran the club, and his wife, Margaret, used to hang out. There was a little room there where they’d have folk music, then you’d walk up another flight of steps and there was a room where rock and roll bands used to play, where they had jam sessions. They had a

wall with amplifiers always set up and a drum set, and people used to jam there. That’s where Springsteen formed a band called Child. There used to be these great things called Battles of the Bands at CYO dances and at these places then called Hullabaloo Teen Clubs that used to be all throughout New Jersey. At the Battles four or five bands would set up in the same room, maybe a gymnasium, and play three or four songs apiece, and the crowd would pick the winner, which would then come back and play three or four songs. It was the perfect way to get the best musicians from the area all under one roof: Then they’d split off and form one band. That’s where Springsteen got the idea how to form Child, at The Upstage. I met Southside Johnny Lyon, Steve Van Zandt, Garry Tallent, David Sancious, Vini “Mad Dog” Lopez, who was a little older than the other guys. He’d started in a band called Sonny and the Starfires, in 1965 or ’66 with Sonny Ken, whose real name was Kenny Rutledge. Bruce used to go see them play. Sonny had these moves—Bruce used to sit there and watch his moves and then sort of use them onstage himself. There was this whole Shore band thing that started around that time, and that’s how Vini first met Bruce.

VINI LOPEZ: I first met Bruce when I was looking for a guitar player for a band I was in called The Moment of Truth. I’d heard about Bruce. We’d played a Battle of the Bands and Bruce was in the other band, but he wasn’t really that good. As the years went by, though, we’d keep hearing about this guy Bruce Springsteen. So I went to see him again, at a club he was playing, some Italian American Club in Long Branch.

He’d gotten a lot better. One night I walked into The Upstage and there he was onstage, playing. And yeah, yeah, now he was good, he was real good. He invited me and my guys to jam that night. Me, Danny Federici—he was in the band that I was in at the time—and little Vinny Roslyn was there. We all jammed and we were pretty damn good.

VIOLA: Bruce tried out a lot of different people jamming for Child until he got the people that he liked. Vini Lopez on drums, Vinny Roslyn on bass, Danny Federici on organ, and Bruce on guitar. After a couple of months, Bruce kicked Roslyn out and replaced him with Steve Van Zandt. Van Zandt was actually a guitar player who learned the bass in order to join the band. Bruce really wanted Steve in the band.

They used to play a little original material, stuff that Bruce wrote. They also did some songs of Bill Chinnock, who was at the time in the Downtown Tangiers Blues Band. Child used to play on the beach a lot, but there was really no place for them to play where they could make money because the clubs in the area, especially South Asbury Park, were only into Top 40 and didn’t want any original material. Sometimes the band managed to land a gig opening up at the Sunshine In for the main act.

There was a place called The Student Prince where Vini went in and told the management they would play for the door, just to get a place to play. It was around this time, during the Child period, Bruce began to really write songs. Prior to that, he wasn’t writing very much at all. I remember this one song he wrote early on, “Garden State Parkway Blues, ” which told the story of a whole day in a guy’s life. It was about a thirty minute song Bruce tried to develop long songs because the band would get jobs in bars where they’d have to play five sets a night, and he figured one long song would take care of a whole set. Some other long songs he wrote during that period were “The ~Wind and the Rain, ” “Send That Boy to Jail” . . . [“Send That Boy to Jail”] was one he developed after the band played the Clearwater Teen Club, and the police came in and tried to stop the dance. Danny Federici had pushed his Leslie [organ amplifier] over, and it fell on the top of the chief of police’s head. Danny had to go into hiding after that and actually cut his hair. That was the basis for that song. Bruce later changed the name to “The Judge Song ” He also did a song called “Resurrection, ” which was sort of a warpo-Catholic Church kind of thing

There is some question as to the origin of both Child and Steel Mill, particularly as to who began which group and who asked whom to join. According to some versions of the story, Bruce changed the name of his group to Steel Mill and incorporated Lopez, Federici, and Roslyn into the group. Vini Lopez remembers it differently.

LOPEZ: I was the one who asked him to join us. I don’t care if Brucie knows it, if Mike Appel knows it, or whoever. I asked Bruce to join my band and I brought him to Tinker [West]. It was me, Danny, little Vinny, we were already a working band. Bruce wasn’t the only one down there trying to make it. There were tons of guys.

Billy Chinnock, for instance.

Lopez’s reasons for claiming leadership are twofold. He still feels he was overlooked for his role in the formation of what was, essentially, the first incarnation of the E Street Band that played on Bruce’s first two albums, and he claims to have never collected a cent in artist royalties.

SPRINGSTEEN: I was the lead singer and band leader. You know, sort of unspoken.

VIOLA: He played this Les Paul guitar, and he wore his hair real long Morally and philosophically, he was into the sixties thing. But not the fashion or the drug thing, even though it was happening all around him. I always believed he wore his hair long to hide his face because he had a really bad acne problem, really severe. The hair probably made it worse.

Anyway, he got known for playing this lead guitar, and he quickly became “King of The Upstage, ” so to speak. He was also the first person from that scene who never really worked a “day ” job. Everybody else did but not him . He never ate much, he’d crash at people’s places, he’d sleep on the beach. He was always saying he ,was going to make it as a musician, that was his big thing, I’m going to make it, I’m going to make it…. Bruce began developing an interest in, of all things, surfing. After living for a while with a couple of surfers, various musicians, including Miami Steve, and other locals, he moved into the attic above a surfboard factory owned by Steel Mill’s manager, Carl Virgil “Tinker” West, a native Californian. Bruce formed a close relationship with Tinker, which may have been the motivation for Springsteen’s taking up surfing: a way to please the newest father figure in his life. West took the young nineteen-year-old first into his house and then into his heart by accepting the role of surrogate dad and offering to teach Bruce how to drive.

S P R I N G S T E E N: I think I was living with Miami Steve, this h a s got to be ’68, ’69, somewhere in there, at 610 Seventh Avenue, possibly, in Asbury Park. It was a third-floor place, like the attic…. It wasn’t a whole lot. I was with Mad Dog [Lopez] when I met Tinker. He had this surfboard factory. We needed a place to rehearse, and he said we could rehearse there. He got us two speakers and said he would be the manager. We said okay. He said he’d just try and get us jobs. He said [it was] ’cause he liked the band.

No formal financial arrangements were agreed to. Bruce, Lopez, and Miami Steve occasionally worked in the surfboard factory to pay their rent, as no one had very much money. Apparently, it wasn’t a hardship to Tinker, who seems to have genuinely enjoyed the boys’ company.

V I O L A: The band actually played Richmond, Virginia, ~quite a bit and became very popular down there. There were some concerts that became legend in the Richmond area. One took place on the top of a parking deck. Another took place at a club called The Back Door. Richmond became the second home for the Asbury Park guys. Even the posters the band had printed up for Richmond always said, “Featuring Bruce Springsteen,” because of the following he’d developed down there.

M I K E A P P E L: Years later, we played in a theater in Richmond, Virginia, in 1973. We sold the theater out right away, much to my amazement. It was unthinkable that Springsteen could sell out four thousand seats at that time anywhere in the world! But in Richmond, Virginia, he could do it, and he did.

VIOLA: And of course, they continued to play at The Upstage, which only held a couple of hundred people. The same people went there all the time. Musicians would show up after their regular gigs to hang out. It was quite a scene. They’d meet and oftentimes jam. It was wild, very psychedelic. A lot of people would take acid and wind up taking their clothes off. There were Day-Glo paintings all over the walls.

And as the months went by, Bruce became known as this guy with this wild stage presence. He pretty much did all the lead singing. Vini did one or two songs, Danny never sang much, Van Zandt sang one or two and some backup, but he never had that strong of a voice.

S P R I N G S T E E N: We used to play from Jersey down to Carolina, for a lot of colleges. I don’t know, ten, twenty, I don’t know how many. Actually there was only a few that we played all the time, you know. Like we were popular in a small area. We were very popular. We played a few clubs. Just joints out on the highway. I don ‘t even remember their names. We wanted to play anyplace.

The largest audience the band played to was a four-thousand seat sellout, in Richmond, Virginia. Tinker handled all the financial affairs of the group. He booked the gigs, collected the money, and paid the members of the band. They didn’t make very much, and whatever came in was divided equally among them. One time Tinker decided to drive cross-country to his home state of California and offered to take Bruce and the band along. While visiting his parents in San Mateo, Springsteen took the band around to a few local spots. The reaction was decidedly mixed for the scruffy East Coasters in the land of milk and Beach Boys. Their first gig was in that pantheon of West Coast pretension, the self-awareness institute known as Esalen, located south of San Francisco. Springsteen later recalled the experience as being like “some crazy party. ” The group also played a few clubs around Berkeley, and there was talk among some of the members of maybe moving permanently to San Francisco, home base to Jefferson Airplane, The Grateful Dead, Moby Grape, and other successful sixties rock groups.

It wasn’t the first time the band had considered relocating. Because of its huge popularity in Richmond, the group regularly thought of moving its home base there. Now, having had a first taste of California, the band was determined to return. They did, early in 1970. Springsteen and the boys played The Matrix Club in Berkeley where they caught the attention of Philip Elwood, then a rock critic for the San Francisco Examiner. Elwood’s rave review came to the attention of Bill Graham, who offered the band studio time and, on the strength of their demos, a recording contract.

SPRINGSTEEN: [We were in] California and somehow we got some time at Bill Graham’s studio. We had three songs [we recorded on demos]. A song called “The Train, ” I think. A song called “The Judge. ” A song called “Georgia. ” We did play audition night at The Fillmore West. We played and [Graham] told us to come back the next week. We went back and played again because somebody cancelled out, I think, and then Tinker said that we had a chance to make a demo. Everybody was pretty excited. [It took] a couple of hours. And Tinker was there, two other guys that ran the knobs, you know, and that was it. I don’t think anything was done with [the demos]. Very little. Nothing came of it. Tinker told me they wanted to make some deal but that it wasn’t good. I think he said something about they were going to give us, like, fifteen hundred dollars or something like that. He didn’t say what it was for. I wasn’t overly interested at the time because I didn’t have the confidence in the band that other people seemed to have, you know, and . . . I didn’t, like, jump on it, you know . . . I was sort of laid- back from it, you know.

The band eventually returned to the Jersey Shore. Several articles began appearing in the local press, praising the band and Bruce in particular. “Springsteen’s songs are blues and they’re solid rock,” wrote Joan Pikula in one Asbury Park daily. “They’re physical and they’re political. They’re gentle and they’re angry. And, most importantly, they’re really fine. [The band] did ‘Black Sun Rising,’ ‘I Just Can’t Think,’ ‘Resurrection,’ ‘American Under Fire,’ . . . and somewhere in the middle the first strains of funny ‘Sweet Melinda’ brought a round of appreciative applause from an audience obviously familiar with the song—a pretty good sign for a group which hasn’t (through choice) recorded yet.” Perhaps the expansion of Bruce’s geographic realm had something to do with it, or the exposure to the emerging sound of West Coast rock. Whatever the reason, in spite of the good reviews, Springsteen determined the band’s music had lost a step somewhere. Besides, the Shore scene had turned ugly. At one concert that summer, three thousand youngsters took on the local police force, a melee that resulted in the arrest of twenty-one people on various charges of assault, offensive language, and narcotics. The 1970 summer race riots in Asbury Park were perfectly in synch with the urban unrest all across the country. The idyllic sixties had turned seventies-idiotic. The murder of four students at Kent State that spring signalled a summer of war-weary bitterness, helpless cynicism, random violence, and

meaningless death to young America. In the uneasiness of those tense nights on the Jersey Shore, the music got lost, and Steel Mill fell apart. Their final performance took place in January of 1971, at The Upstage. The next day, Bruce approached Tinker and told him he was leaving the group.

S P R I N G S T E E N: I said I was breaking up the old band, I was going to start a new band. He said, “Gee whiz, you know, we might have some opportunities for the old band. ” All I remember at the time, there was something about Paramount Records. I met a guy [from the label] who came down to a show. He said the band was good, he said he liked it. I met him a couple of times.

Nothing came of that, nor the Graham offer, which was fine with Bruce because he wanted no part of either.

SPRINGSTEEN: I didn’t think the band was good anymore. It wasn’t what I wanted to do.

In order to attract new musicians, Bruce put an ad in the Asbury Park paper for two singers, a trumpet player, and a saxophonist. The new group slowly came together, with Vini Lope and Miami Steve held over from Steel Mill, two new backup girls, two horn players, saxophonist Clarence Clemons, and a bass player by the name of Garry Tallent. Bruce called the new group Dr. Zoom and the Sonic Boom, and as quickly as it came together, it, too, fell apart.

VIOLA: Zoom wasn’t really a band; it was more like a circus. They had a live Monopoly game going onstage: Southside Johnny was the ringmaster, two or three drum sets, a whole new set of musicians, and I can ‘t remember the name of one song the band ever played. I think they ended up doing only four or five gigs, but it was wild. No one had ever seen anything like that. And of course, Bruce was the center of attraction of all that was going on.

By this point, he’d built something of a local name for himself in the area, where everybody felt that if anybody was going to be able to make it, it was going to be him. But again, this was primarily as a lead guitarist, not so much as a writer or a singer.

Dr. Zoom was followed by the Bruce Springsteen Band.

S P R I N G S T E E N: Steel Mill was a band that rocked. It got you on your feet, set you in motion, and kept you there. This band rocks a little differently—more in the rhythm and blues vein than rock and roll, sometimes with a gospel blast that really moves. And it swings. It’s mellow and quite subtle, sending out layers off at, complex patterns.

The Bruce Springsteen Band played the same bar trail along the Jersey-to-Carolina route and the by now reliable Richmond circuit.

SPRINGSTEEN: We stayed in a hotel in Nashville once. That was because somebody invited us down there. By this time we ‘d made friends. You ‘d go to a town, you ‘d have somebody ‘s house to stay at. A lot of times some people would just sleep in the back of the truck.

While they were in Virginia, some interest was expressed by the owner of Alpha Studios about the possibility of recording the band. Davey Sancious, the newest member of the group and a studio-session piano player, introduced Bruce to the head of the studio, who put a carrot out but failed to get a nibble. Once again, it seems Springsteen had lost interest in a group he’d put together. The Bruce Springsteen Band played a total of about a dozen gigs.

SPRINGSTEEN: We stopped getting some jobs and then Vini socked somebody and quit, and I sort of, you know, went back to a five-piece band . . . sometimes to a seven. We never made any money. It was, like, tough to get work in those days, especially doing what I was doing . . . We worked [regularly] in a bar in Asbury, The

Student Prince. Me, Steve, Garry, Mad Dog, and Davey Sancious. [We played for about] one hundred and fifty people for a dollar at the door.

VIOLA: The Bruce Springsteen Band was actually the immediate progenitor of the first E Street Band. David Sancious and Garry Tallent had come over from other Shore bands, Moment of Truth and Sundance Blues Band, respectively. Bruce brought them into his band. Lopez remained on drums and Van Zandt switched over to guitar because Garry was really a bass player. The Bruce Springsteen Band was his attempt to do a much more sophisticated hybrid of the music of Santana and The Allman Brothers, a blues-based rock band.

After Vini Lopez punched one of the horn players in the mouth and knocked his tooth out, Bruce got rid of the horns and the girls and dropped it down to the five-piece. They used to do stuff like “I Remember, ” there was a song about an outlaw, “The Band’s Just Boppin’ the Blues”; he did this amazing instrumental, double-lead guitar, metal version of “Darkness Darkness, ” The Youngbloods thing “Darkness Darkness” was amazing to see and hear. The Bruce Springsteen Band stayed together about six or seven months. The highlight of their existence was when they got to open once for Humble Pie.

All this time, too, Bruce had been recording in Tinker’s surfboard factory, where the band lived. It was a real small place with a &t roof that was so small one of the members lived in the bathroom, one lived in the front office. It was real tight. They did a lot of recording there. There was actually some exciting stuff. They did one slow version of Dylan’s “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue, ” which had a lot of lead guitar on it that was really good. They also recorded some original stuff of Bruce’s, but he was never really happy with the results. It was more a learning experience, so he could hear how he sounded on tape, than anything else.

In 1971 a vote was taken and Tinker was out. It was left to Bruce to tell him.

SPRINGSTEEN: 1 remember at the time we weren’t working very much, and I don’t exactly remember what triggered the situation. All I remember doing was being in a discussion about it. I know there was a big argument between [Tinker] and Vini in this bar, and Vini, you know, was screaming . . . [Later on] I remember [Tinker] was under his truck, fixing it, when I came by and told him everybody decided that they didn’t want him to manage us anymore. He said okay, and that was it.

VIOLA: After the Bruce Springsteen Band broke up, nobody heard from Bruce for quite a while, six months or so, during which time the other band members all went their separate ways.

Miami Steve took a job working construction before joining the Philadelphia-based doo-wop group The Dovells, famous for two hits, “The Bristol Stomp” and “You Can’t Sit Down.” Springsteen thought this was the greatest thing, to actually be in a real rock and roll band. Garry Tallent found a job teaching music. Clarence Clemons worked with street kids.

When Springsteen finally reemerged, Ken Viola recalled, he announced to a group of his friends, “I now know how Phil Spector makes records.” He went on to describe in detail the way he thought Van Morrison got his sound on “Moondance” and Dylan his on “One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later),” on Blonde on Blonde. Yet for all his enthusiasm, ability, and growing awareness of the mechanics of rock, music was, in reality, little more than a vocation to Springsteen, a teenage working-class rite of passage, a way of life with no focus and no future.

A life, however, about to undergo a staggering change with the arrival of another young guy out to make it, who, once his path crossed with Bruce’s, formed a partnership with him that made rock history.

The other guy’s name was Mike Appel.

http://feeds.feedburner.com/Tsitalia