Seconda ed ultima parte di quest’ articolo del 1985.

The only exception to the small venues was three nights in August at New York’s Madison Square

Garden, the scene of the disastrous set five years previously when he had opened for Chicago.

History did not repeat itself. The three nights were a triumph, culminating on the last night in Bruce’s

mother herself appearing on stage to drag him back in mock reluctance for an encore.

Springsteen was taking his music to the people it was meant for, the people who were the characters

in his songs. He was singled out at this time as the prime exponent of a new musical development,

‘Blue Collar rock’. Cynthia Rose wrote a telling essay on the phenomenon for the History Of Rock

magazine: ‘[It] is a critical term, disseminated by various rock critics who possess “white collar”

credentials. It was coined to deal with a number of American artists who were selling solidly (in the

case of Bruce Springsteen, spectacularly) and had achieved somewhat heroic stature; all with

“traditional” rock songs, whose lyrics featured girls, cars, rebellion and the radio…. Several supposed

similarities linked those artists (Springsteen, Tom Petty and Bob Seger). The great unspoken,

unwritten one was that they lacked “proper” (i.e. white collar) educations: that their smarts were

street smarts, their language limited to that of the truck stop, shopping mall or suburban housing

tract. That they were tough and randy rockers in the guise of people’s heroes – spokesmen and role

models for the little guy and his girl.’

In Springsteen’s case, that is certainly applicable. He was almost cocky about his lack of real

education, revelled in his role of rock’s noble savage (expressing direct emotion without the

hindrance of proper education) and phrasing his message and narratives in ‘traditional’ rock terms. It

was a point which David Hepworth amplified in a 1982 essay: ‘Springsteen has been called a

reactionary . .. he has shamelessly poured every last iota of his craft, enthusiasm, humour and

passion into giving back to the people what he himself got from the likes of the Drifters, Smokey

Robinson and the Who . . .’

Indeed, in America in the late seventies, people were looking for someone who offered hope, a

figure of integrity following the chicanery of Watergate. In politics they got Jimmy Carter, who at

least got off on the right foot by quoting Bob Dylan in his inaugural address. In rock’n’roll, they got

Bruce Springsteen. His concerts offered more than just good value for money; they became group

expressions of solidarity and hope, with Springsteen placing trust in his audience, making

spontaneous leaps into the heart of the crowd.

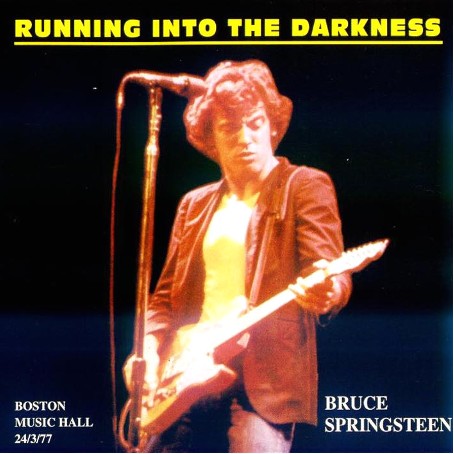

In Britain on the other hand, by the time of the release there of Darkness On The Edge Of Town the

majority of people had all but written Springsteen off. They remembered the hype of 1975, and there

had been nothing since then on record to substantiate the pretender. Certainly, there were stories of

the marathon gigs in the States, and a steady trickle of bootlegs. Certainly, there were pieces, too,

like Tony Parsons’ heartfelt New Musical Express interview of October 1978: ‘Kid, I’ve seen ’em all….

But this ain’t just the best gig I’ve ever seen in my life, it’s much more than that. It’s like watching

your entire life flashing by, and instead of dying, you’re dancing!’ But at the end of 1978 UK fans had

other things on their mind. The punk revolution of 1976 had entirely altered the face of the British

music scene. By 1978 the economic sky had become darker and gloomier than that which had seen

the Technicolor panache of Born To Run three years before. The New Wave had throbbed on its own

manic energy, and had produced its own spokesmen. There was the feeling that the hero worship of

remote American superstars – particularly those that sang about cars and cruisin’, and called every

woman ‘baby’ – was over. There were instead, real issues and dangers, which the young punks

confronted. A political swing to the Right, overt racism in British society, the intolerable level of

growing unemployment, all had to be confronted and indeed were confronted by the new

generation of musicians: Tom Robinson’s scathing ‘Winter of ’79’, Elvis Costello’s biting indictments

of fascism on ‘Less Than Zero’ and ‘Night Rally’, the Clash’s accusatory ‘I’m So Bored With The USA’,

the Jam’s attack on the odious National Front on ‘Down In The Tube Station At Midnight’ and the Sex

Pistols’ howl for ‘Anarchy In The UK’.

By now many British bands were no older than their audiences. Heavily political, eagerly embracing

reggae, spurning orthodox rock venues, scornful of fashion, lambasting the established old guard of

rock notables (Rod Stewart, Mick Jagger, Elton John, Genesis), the New Wave had no need for

museum pieces like Bob Dylan or the Pink Floyd. After the initial Luddite assault, which recalled the

heady days of Merseybeat, with every week throwing up dozens of new bands, the New Wave

established its own hierarchy, populated by concerned and articulate writers like Elvis Costello, Paul

Weller, Joe Strummer, Ian Dury and Difford and Tilbrook. Punk had given rock’n’roll a necessary

kick in the right direction, and the last thing anyone needed then was Born To Run II. But that is not

what was delivered, and the new sounds were dark and unlike the previous Springsteen. Rather than

writing him off, Darkness gave Springsteen a lot of new UK fans. It mirrored the turmoil at the end

of the seventies, and confronted contemporary issues head on. At a time when many rock idols were

dismantled and rendered obsolete, Springsteen proved in the tough British musical climate that he

had weathered the storm, and emerged with his principles and credibility intact.

This son of a New Jersey coach driver showed that he could convey sentiments and emotions which

would reverberate around the world. It was, in fact, his origins which enabled him to do this. Tired of

pretentious concept and flimsy philosophical albums, the fans found a gritty honesty and

straightforwardness in Springsteen. Tired of arrogant and aloof stars, they found a singer who was

affable and courteous offstage. Tired of rock music hung around with ‘art’ labels, they found a nonintellectual

who once said, ‘I was brought up on TV…. I didn’t hang round with no crowd that was

talking about William Burroughs!’ This was a man who shared their disillusionment, who also said,

‘When the guitar solos went on too long at the end of the sixties, I lost interest!’

Although political in its broader sense, Springsteen had never allied himself directly with any political

cause. His songs revealed a humanitarian, an artist with a concern for the issues of his time, but never

along orthodox party lines. So it was with some sur,prise that it was learned that Bruce Springsteen

and the E Street Band had agreed to play two charity shows on behalf of MUSE (Musicians United for

Safe Energy) in September 1979. The concerts were a response to the near-disaster at Three Mile

Island in Pennsylvania earlier in the year, when the nuclear process plant leaked and threatened to

explode, causing a hasty evacuation from the area. Springsteen had been friendly with Jackson

Browne, one usual rumours circulated: Springsteen was to play the Marlon Brando role in a re-make

of The Wild One; he was paralysed in hospital; he was making albums with Rickie Lee Jones and

Stevie Nicks; he was to be chosen as New Jersey’s ‘Youth Ambassador’ (he wasn’t, but ‘Born To Run’

was chosen as the state’s ‘unofficial Youth Rock Anthem’). In fact, there was a whisper of truth in the

hospital rumour as he had hurt his leg in a minor motor cycle accident, but this did not stop him

getting back into the studio to record his fifth album.

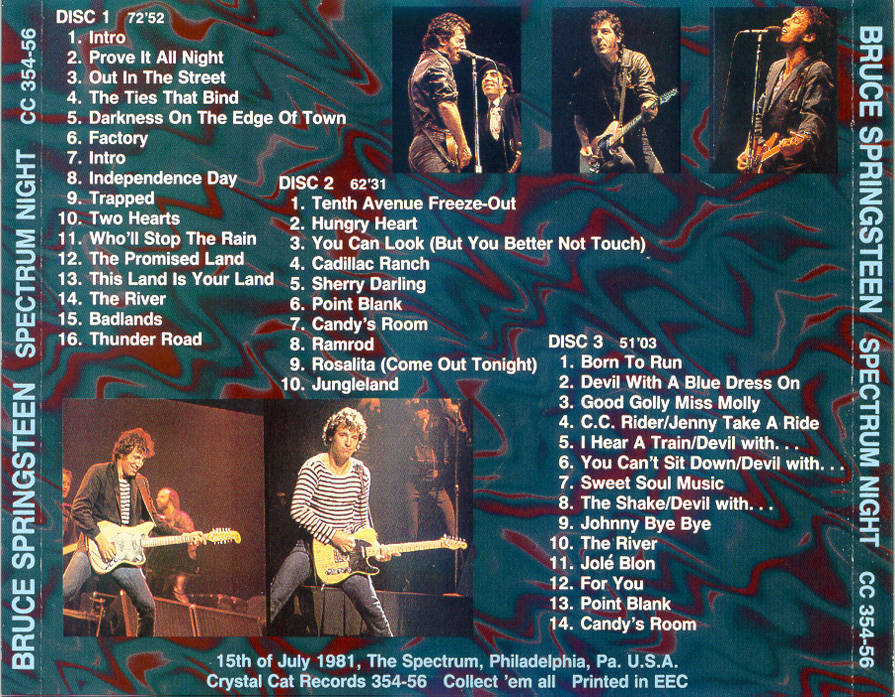

It was another long job. Work on The River started in April 1979, but the record did not see the light

of day until October 1980. As a reward for the time since Darkness On The Edge Of Town it was a

two-record set. In fact, it is one of the few double albums in rock to fully merit four sides, and still

stands as the best available insight into the Springsteen phenomenon. This was recognised by its

selling 2 million copies. Its strength lies in its diversity, with twenty songs covering the spectrum of

his writing, from the pensive ‘Independence Day’ and ‘Wreck On The

Highway’ to the exuberant ‘Sherry Darling’ and ‘You Can Look (But You Better Not Touch)’. Its

span rangcs from a chilling ‘Point Blank’ to a throw-away ‘Cadillac Ranch’. It was a return to the

intensity of his first album seven years before, as if this was the one that Springsteen had to prove

himself with, and as a result poured everything into it. As Paolo Hewitt wrote in his Melody Maker

review: ‘Listening to it is like taking a trip through the rock’n’roll heartland as you’ve never

experienced it. It is a walk down all the streets, all the places, all the people and all the souls that rock

has ever visited, excited, cried for and loved.’

Springsteen had never sounded cockier or brasher on the rockers, or more reflective on the ballads.

As if marking his turning thirty during recording, The River offers a reconciliation between the

glorious optimism of Born To Run and the sombre introspection of Darkness On The Edge Of Town.

It marks a bridge between innocence and experience. The songs find Springsteen viewing the lives

and circumstances of his contemporaries with compassion, but with an objectivity which makes them

universally applicable. It acknowledges that the stark issues which were so clearly defined in youth,

grow blurred and confused with age.

Springsteen saw the album as an austere reflection of the times, but characterised by occasional

delights. The characters here are in danger of being crushed, of standing, drained of motivation and

ambition, but sustained by the possibility of dreams. He told Robert Hilburn of the Los Angeles

Times soon after the album was released: ‘Rock’n’roll has always been this joy, this certain happiness

that is, in its way, the most beautiful thing in life. But rock is also about hardness and closeness and

being alone. With Darkness it was hard for me to make those things coexist . . . I wasn’t ready, for

some reason within myself, to feel those things. It was too confusing, too paradoxical. But I finally

got to the place where I realized I had paradoxes, a lot of them, and you’ve got to live with them….

What happens to most people is when their first dream gets killed off, nothing ever takes its place.

The important thing is to keep holding out for possibilities…. There’s an article by Norman Mailer

that says, “The one freedom people want most is the one they can’t have: The freedom from dread.”

That idea is somewhere at the heart of the new album, I know it is.’

Springsteen recognised that as people grow older – or, indeed, grow up – they have to make

compromises, and learn to live with them. It’s inevitable, whether in relationships, jobs, aspirations,

dreams. But there was still a vestige of the romantic clinging to him, saying that you must have

dreams, something to aim for, otherwise life itself loses all meaning, and becomes an empty charade.

He said to the New York Sunday News: ‘You can’t just be a drearner. That can become an illusion,

which turns into a delusion, you know? Having dreams is probably the most important thing in your

life. But letting them mutate into delusions, wow, that’s poison.

Dreams are there to be attained, not sustained, plateaux on the way up our individual Everests. Yet,

ironically, the essence of dreams is their ability to remain untouched or unattainable. The lines from

the album’s title song are especially significant: ‘Is a dream a lie if it don’t come true/Or is it

something worse?’

However, the lighter side of Springsteen was amply represented in The River, from the glorious

Searchers-influenced opening chords of’The Ties That Bind’, through an exultant ‘Sherry Darling’, a

defiant ‘Out On The Street’ and a gleefill ‘Crush On You’ and ‘I’m A Rocker’. Songs like ‘Hungry

Heart’, ‘Ramrod’ and ‘Cadillac Ranch’ are supremely crafted examples of high energy rock’n’roll. But

Springsteen’s strength has always been his variety, the ability to alter moods simply on the strength

of his songs. The contrast imbues the darker side of the album with a greater power and durability.

The characters on the album are people who have been ground down, but are still kicking. They

recognise the bitterness of the system which produced them, and how they have virtually outlived

their usefillness, so they escape, or try to escape, whether to the river, the highway or the edge of

town. What Springsteen so admires is their tryin,g. If any one line from the album epitomises

Springsteen’s realisation of those changes, it is ‘Point Blank’s’ valedictory: ‘I was gonna be your

Romeo, you were gonna be my Juliet/These days you don’t wait on Romeos, you wait on that

welfare check.’ In those ~vo bitterly resigned lines, Springsteen bids a sad farewell to that era of lost

innocence, goodbye t~ Spanish Johnny (‘Like a cool Romeo, he made his moves’) and the Romeo of

‘Fire’. A goodbye, too, to his youth. It was now time to face the harsh realities of adult life.Even the

rockers are peppered with marvellous throwaway lines: ‘So you fell for some jerk who was tall, dark

and handsome/Then he kidnapped your heart, and now he’s holdin’ it for ransom’ (‘I’m A Rocker’),

‘She makes the Venus de Milo look like she’s got no style/She makes Sheena of the Jungle look meek

and mild’ (‘Crush On You’) and the ironic last verse of ‘You Can Look (But You Better Not Touch)’.

But although The River contains the best of Springsteen’s recorded work, it also has some low points.

It is difficult to take ‘Drive All Night’ seriously- driving all night for a pair of shoes? The song’s

length, and Springsteen’s hammy delivery, pall beside earlier versions of a similar theme, like ‘Streets

Of Fire’ or ‘Something In The Night’. ‘Stolen Car’ descends quickly into predictability, with the

unconvincing lines: ‘She asked if I re membered the letters I wrote/When our love was young and

bold/ She said last night she read those letters/And they made her feel one hundred years old.’ And

‘Out In The Street’ finds Springsteen at his most brash and feeble: ‘When I’m out in the street, I walk

the way I wanna walk . . . I talk the way I wanna talk.’

It is on a song like ‘Wreck On The Highway’ that Springsteen displays his strengths. It is stripped

down to the bone lyrically and musically, and acts as an iconoclastic coda to the album. The scope and

implication of the song are far broader than the story of a man witnessing somebody dying in the

aftermath of a car crash. By implication, Springsteen raises questions about our ideas of mortality, of

‘the ultimate question’ of life and death, of the haphazard snuffing out of an individual candle. But so

restrained is his performance, and so deft his writing, that the song never becomes pretentious.

‘The Price You Pay’ is an epic song, in both ambition and achievement, from the crashing drums

which introduced it, to Springsteen’s triumphant vocal finish. It touches on the Western myth so

beloved by John Ford, and sounds as if it was intended to be set in Monument Valley: ‘Do you

remember the story of the promised land/How he crossed the desert sands/And could not enter the

chosen land/On the banks of the river he stayed/To face the price you pay?’ The song touches on

the compromises we must make, and the dreams which sustain their purity. A man stands alone,

defiant, determined to fight for what he believes in, aware that sacrifices have to be made, and

willing to undergo purgatory for the glory and the dream.

The title track sprang from Springsteen’s conversations with his brother-in-law, and shows a

complete understanding of the realities of the new recession. His sister had married before she was

20, and started a family soon afterwards. Her husband, a construction worker, lost his job and the

family went through a terrible time. ‘The River’ is about their experiences, and the fortitude that

enabled them to pull through and later to thrive. To Springsteen such people are the real heroes of

today. The song is full of bitter intensity, and is very much of its time, but one which accommodates

the past, recalling carefree younger days in the final verse, without glamorising them. It is an acute

piece of narrative, conclusive proof that Springsteen had overcome the sentimentality which had

threatened to choke his development.

It was one from the heart, as was ‘Independence Day’ – a white flag flying over the no man’s land

which exists between parents and their errant children, which lasts through the years, as successive

generations try to come to terms and cope with that distance. The very understatement of the song

exonerates Springsteen from many of his previous excesses. He carefully, touchingly, delineates that

feeling, that time, when all men must make their way, come Independence Day.

As ever, with any Springsteen album, there was a lengthy, agonising search to decide the final

running order, made doubly difficult because of the 20 songs intended for it. Finally, Springsteen

himself, Jon Landau and Miami Steve managed to agree on the sequencing. So the Drifterish

resignation of’I Wanna Marry You’ slots neatly between the exuberance of’You Can Look . . .’ and

the melancholy ‘The River’, just as ‘Fade Away’ fits perfectly between ‘I’m A Rocker’ and ‘Stolen

Car’.

The River gave Springsteen his first real hit single – ‘Hungry Heart’ reached number 5 in the US

charts in November 1980; ‘Born To Run’ had, incredibly, only got to 23. It also brought him a whole

vast new audience. The album was awarded a Platinum disc (for selling over one million copies) and

entered the Record World Top Ten at number 2, and Billboard’s at number 4. Such was his success

that only five albums into his career the press gave him one of their greatest accolades, and started

looking out for ‘New Springsteens’!

Not everyone was convinced, though. NewMusical Express’s Julie Burchill remarked that ‘There’s no

bore worse than a Bruce bore!’ and several other critics had a go at him: they thought he was

sentimental and juvenile. He was accused of male chauvinism, constantly referring to women with

the demeaning ‘baby’. These critics viewed his coy attitude to fame as a sham, and remembered the

‘future of rock’n’roll’ quote with bitterness. They also found him tiresomely evangelical about

rock’n’roll itself in interviews, Frances Lass wryly asking in London’s Time Out: ‘What would he have

done if he’d failed his driving test?’ Some of those who had previously liked his work carped about

the constant overpowering use of car imagery and symbols in the new album.

The criticism of him for excessive use of car imagery has been made against other albums. The

justification is that the car is a prime American symbol, and Springsteen has countered: ‘I don’t write

songs about cars. My songs are about people in those cars.’ Certainly, he uses the car and the

highway as recurrent symbols, but this springs from his background and environment. It is unfair to

criticise a writer for his stock of imagery if he expresses deeper emotions through it. Springsteen

simply takes a recognisable icon of America – the car – and utilises it to his own imaginative ends. It

can work to dazzling effect (‘Racing In The Street’, ‘Wreck On The Highway’) or be numbingly

amateurish (‘Drive All Night’).

The hostile critics were, however, in a minority, and the album was well received by the public. With

The River in the shops and on the charts, Springsteen hit the road for his most gruelling tour to date.

It was to last twelve months, cover thirteen countries, and include 132 gigs. Two months into it, in

Philadelphia, he took the stage on the day after one of the most fateful dates in rock history 8

December 1980. That night, John Lennon had been murdered in New York. Clearly shaken,

Springsteen addressed the crowd: ‘It’s a hard night to come out and play when so much has been lost

… if it wasn’t for John Lennon, we’d all be in a different place tonight. It’s a hard world that makes

you live a lot of things that are unlivable. And it’s hard to come out here and play, but there’s

no~hing else to do!’ Springsteen was visibly shocked by the death of a man he had never met, but

whose music had started him on his own career – ‘I got the same musical background as most 31-

yearolds: Stones, Beatles, Kinks.’ He finished that night with ‘Twist and Shout’.

Appropriately, when The River tour coiled into Europe in April 1981, the first date was in Hamburg,

the city where the Beatles had paid their dues in cellars along the Reeperbahn two decades before.

Promoter Fritz Rau called Springsteen’s visit ‘the most successful in German rock history’. It was a

promising beginning, and the promise was not to be confounded.

of the organizers, for a number of years, and it was at his suggestion that he agreed to appear on a

platform campaigning against nuclear energy.

Springsteen’s immediate reaction on hearing of the incident had been to write a song called

‘Roulette’. It speculated on how Three Mile Island would have affected a man and his family if they

had lived in the area. However, it is not a good song. While managing to evoke a feeling of eeriness

and threat, it is far too paranoid, and subscquently suffers by concentrating on such a specific

incident. The broader aspects of the song, and the possibility of nuclear holocaust, are clumsily tacked

on at the end. Wisely, Springsteen never officially recorded the song, and did not even perform it at

the MUSE concerts at Madison Square Garden.

The MUSE shows of September 1979 were a watershed for the music of the seventics. Therc were five

concerts. Springsteen closed each of the last two, and on both occasions stole the show. He played a

particularly energetic hour-and-a-half set in the second one, giving everything he had as if to

challenge time itself in defiance of the fact that the next day was his thirtieth birthday. But perhaps

the event was looming over him, because in an uncharacteristic burst of temper he swooped on his

photographer exgirlfriend, Lynn Goldsmith, in the front of the crowd, and had her ejected for taking

photographs of him in spite of an agreement that she wouldn’t.

A selection from the concerts appeared as a film, No Nukes, featuring threec of Springsteen’s songs,

accompanied by a No Nukes triple album, which featured two of the other songs he performed –

‘Stay’ and ‘The Devil With The Blue Dress Medley’.

Lined up were the rock establishment of James Taylor and Carly Simon, Crosby, Stills and Nash,

Jackson Browne and the Doobie Brothers, with Springsteen there to provide thc shock of the new.

Even for the unconverted, it’s no contest, with Springsteen winning hands down. From the moment

he makes his first appearance in the No Nukes fiLm, primed backstage, he is the undoubted star of

the event. The resultant film and triple album amply demonstrate just how entrenched and out-oftouch

the old guard had become. Graham Nash, who performed an embarrassing version of ‘Our

House’, unwittingly offered an epitaph for the occasion when he was asked what it was like playing

bcfore Springsteen: ‘Never open for Bruce Springsteen!’ Only Gil Scott-Heron’s passionate ‘We

Almost Lost Detroit’ and Jackson Browne’s haunting ‘Before The Deluge’ come anywhere near

matching Springsteen’s intensity.

He shook the concert to life with an energetic ‘Thunder Road’. But it was the newly written ballad

‘The River’ which was the real revelation. Couched in sombre blue light, and singing with an

intensity that surpassed even Darkness, Springsteen performed ‘Thc River’ at his most sensitive and

charismatic.

The album package was released in December 1979, and the film followed in August of the next year.

The LP was the sole live recording of Bruce Springsteen and the E Strcct Band at the time.

With the now customary two-year lapse between albums the

This Land Is Your Land

The tour was gathering momentum. From Germany it went to Switzerland, France, Spain, Belgium,

Holland, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and finally to Britain.

Any doubts as to whether Springsteen was right for the current climate wcre soon confounded. In

Britain alone over 600,000 applications were received for the total of 100,000 seats available at his UK

shows. Although the deliberate ugliness of the punks was being replaced in a process of reaction by

the narcissism of the New Romantics, Springsteen survived the backlash that had had those who

sympathised with old-style rock’n’roll branded as ‘rockist’. Everyone involved was determined that

there would be no repetition of the 1975 debacle. Jon Landau told Billboard: ‘There was a great deal

of promotion around then. The situation wasn’t properly controlled. This time we wanted people to

know we were hcrc, to see the records, but beyond that we didn’t want to do anything especially

elaborate.’ Where earlier he had met coolness and scepticism, he was now greeted with enthusiasm.

Promoter Harvey Golclsmith, who hanclled the 1975, 1981 and 1985 shows, remembered how

sobering that first visit had been: ‘We went out to dinner afterwards, and he just couldn’t understand

it all. He was used to playing clubs in the US where audiences knew his songs, and went up the walls

for him, but here was an audience just sitting there, saying, “Okay Brucie baby, show me”.’ But this

time it was different.

In the midst of a depression British audiences found a song like ‘The River’ just as applicable to their

own experiences as it was in the USA. During the European leg of his tour Springsteen added Woody

Guthrie’s ‘This Land Is Your Land’ to his set; it seemed entirely appropriate at the start of a summer

that had already seen riots in one black ghetto and was to see a lot more. On the night of Bob

Marleys death, he altered a line to run ‘From California to thestreets of Brixton’.

The songs Springsteen performed in these concerts were an especially eclectic example of the range

he now presented regularly. As well as his own songs, he gave a liberal selection of rock classics: the

Elvis ballads ‘Follow That Dream’ and ‘Can’t Help Falling In Love’, John Fogertys ‘Who’ll Stop The

Rain’ and ‘Rockin’ All Over The World’, Bobby Fuller’s ‘I Fought The Law’, Arthur Conleys ‘Sweet

Soul Music’, the Beatles’ ‘Twist And Shout’, and Jerry Lee Lewis’ ‘High School Confidential’, as well as

Guthrie’s democratic anthem. However, unaccountably, he only performed one song from his first

two albums, ‘Rosalita’.

Springsteen’s reason for including the classics in his shows was not to preserve them in some sort of

rock’n’roll museum, or to show off his knowledge of music. It is because rock’n’roll is his life, and

they are included as a homage, to pay tribute to the great liberating influence the music had on him.

He told Crawdaddy: ‘Sometimes people ask me who are your favourites. My favourites change….

For me the idea of rock’n’roll is sort of my favourite…. We don’t play oldies. They may be older

songs, but theyre not nostalgic…. It’s great right now, it’s great today, and if somebody plays it and

people hear it, theyll love it tomorrow.’ Once again, Springsteen showed that in rock you have to

move on, but in doing so you also have to be aware of what has been before.

Springsteen’s fascination with rock history is not just a matter of memories from his own past. The

past is there for constant exploration. He told Dave Marsh: ‘I go back, further all the time, back into

Hank Williams, back into Jimmie Rodgers…. What mysterious people they were. There’s this song,

“Jungle Rock”, by Hank Mizell. VYhere is Hank Mizell? What happened to him? What a mysterious

person. What a ghost. And you can put that thing on and see him. You can see him standing in some

little studio, way back when, and just singing that song. No reason. Nothing gonna come of it. Didn’t

sell. That wasn’t no Number One record, and he wasn’t playing no big arenas after it either…. But

what a mythic moment, what a mystery. Those records are filled with mystery; theyre shrouded

with mystery. Like these wild men come out of somewhere, and man they were so alive. The joy and

abandon, inspiration. Inspirational records.’

The European and Scandinavian concerts impressed even his critics with their commitment and their

length. It was a refreshing change after years of American stars going there with no apparent desire

other than to make money, and after several tours by inferior musicians with less integrity.

Springsteen’s performance style, his long monologues, and his affability particulary captivated

European audiences, who had never experienced anything like it before. After the European concerts

Springsteen and the E Street Band retumed to the States for an anti-nuclear benefit at the Hollywood

Bowl, followed by another three months of touring, once again crossing the country from New

Jersey to California. He added several new interpretations to the set – Woody Guthrie’s ‘Deportees’,

the Byrds’ ‘Ballad Of Easy Rider’, Creedence Clearwater Revival’s ‘Proud Mary, Frankie Ford’s ‘Sea

Cruise’ and Tommy James’ ‘Mony Mony’. By the time they had finished they had been seen by more

than a million people, performing to capacity crowds. But Springsteen tours are not just planned as

financial ventures. Touring for a large group like the E Street Band was an expensive business, and

when Jon Landau was asked about this, he replied: ‘Bruce Springsteen doesn’t usually make decisions

on a profit and loss basis.’

In the lull after the tour, Clarence and Miami Steve worked on solo albums, and Max Weinberg was

hard at work on a book about rock drummers. Of all the E Street Band, Miami Steve was closest to

Springsteen in his devotion to rock’n’roll, and missed being on the road. He created an alter-ego,

Little Steven and the Disciples of Soul, which produced one fine album Men Without Women (and a

great single, ‘Solidarity’). But Springsteen himself kept a low profile for most of 1982, emerging for

occasional jam sessions with musicians passing through New Jersey – The Stray Cats, Mitch Ryder,

Dave Edmunds, Nils Lofgren – and for a duet with Jackson Browne at a Rally For Disarmament

concert in New York’s Central Park in June. Otherwise he was involved in lengthy stints in the studio

with the E Street Band, where they stockpiled numerous songs for the follow-up to The River. He

was also spending time in a recording studio in a different role. The week after finishing The River he

had set about producing Gary US Bonds’ album Dedication, which was released in 1981. In early 1982

he was working on the next one, On The Line, which was released in June of that year. This desire to

help an old friend shows that Springsteen’s dedication to rock heritage wasn’t simply limited to

including ‘oldies’ in his stage set. This was all part of that Asbury camaraderie: if someone influenced

you, or inspired your music, you owed that person a debt – which saw Miami Steve, literally, pulling

Lee Dorsey out from under a car in the garage where he worked; and which also saw Springsteen

rescuing Bonds from McDonalds’ openings, and including Ben E. King of the Drifters on the finished

Dedication album. Of the two albums, Dedication was the one that garnered the critical plaudits, with

soulfill renderings of songs by Dylan, the Beatles and Jackson Browne. It also had three new songs by

Springsteen himself. There were also two cracking rockers, ‘Dedication’ and ‘This Little Girl’, and a

Bonds/Springsteen duet on ‘Jole Blon’, a song which Buddy Holly had produced for Waylon Jennings

in 1959. But by the time of On The Line the formula was wearing thin, and Springsteen’s songs were

distinctly sub-standard. Only the exuberant ‘Angelyne’ sounded genuine, while ‘Club Soul City’ was

a clurnsy attempt at a big soul ballad, and ‘Out Of Work’ was almost offensive in its flippancy. The

album prompted accusations that Springsteen was simply using Bonds albums as a durnper for his

own below-par material, and Springsteen did not do any more work with him.

Much more successfill was ‘From Small Things, Big Things Come’, which Springsteen gave to Dave

Edmunds backstage after one of the concerts at the Wembley Arena during the British Tour. It can be

found on Edmunds’ DE7th album. In Edmunds’ capable hands, the song is a classic, tearaway rocker,

closely allied to ‘Ramrod’ or ‘Cadillac Ranch’. One can imagine that Springsteen’s version differs little.

It’s archetypal Springsteen from the word ‘go’. The first verse alone manages to include references to

‘high school’, ‘the promised land’ and ‘hamburger stands’. The killer line comes in the second verse:

‘First she took his order, then she took his heart.’ It skips along in suitably irreverent vein, until the

bridge: ‘Oh, but love is bleeding/It’s sad but it’s true . . .’ before swerving into darker territory on the

final verse: ‘Well, she shot him dead, on a sunny Florida road.’ The motive? ‘She couldn’t stand the

way he drove!’

A detour came when Springsteen donated a song, ‘Protection’, to Donna Summer, which appeared

on her eponymous 1982 album. While ‘Protection’ was not vintage Springsteen, it had its moments:

‘Well if you want it, here is my confession/Baby I can’t help it, you’re my obsession.’ He also donated

a song to Clarence Clemons for his Rescue album, ‘Savin’ Up’, but it was mediocre.

All this activity with different musicians masked a different Springsteen at work. By 1982 he was

being hailed as America’s premier rock’n’roller. With the E Street Band he had been playing all over

the USA and Western Europe to rapturous receptions. But in September, with the release of his next

album, he pulled the plugs out and took everybody by surprise. CBS were astounded when they

received the tapes of Nebraska. Knowing the man’s notoriety for studio perfection, it sounded

astonishingly like a bootleg – scraps of songs, Springsteen entirely solo, demos for the E Street Band.

Anyone expecting a Big Man solo, or any thunderous Mighty Max drumming, was in for a shock.

With the E Street Band back in the swamps of Jersey, Bruce Springsteen had been out on the road

alone, heading straight for the badlands of the Mid-West. He had spent a lot of time just driving

around the country, talking to people, relaxing in the anonymity. In fact, the finished tapes were

hand-delivered by Springsteen to CBS after one such long drive.

Nebraska is one of the most iconoclastic albums ever willingly released by a major rock artist. In

terms of shock and impact, it is comparable to Dylan’s John Wesley Harding and Lennon’s Plastic

Ono Band. Like both of these, it is the sound of an artist baring his soul in public, and doing it in a

radically unorthodox manner.

The seeds for the album were sown when Springsteen read Joe Klein’s biography of Woody Guthrie,

which had inspired him to include Guthrie’s ‘This Land Is Your Land’ at every one of his European

shows. The influence went deep. Talking to Marc Didden prior to the release of Nebraska,

Springsteen said: ‘Why do I cover Woody Guthrie? Because that is what is needed right now.

Everybody is in sackcloth and ashes in my country these days. After Watergate, America just died

emotionally…. Nobody had any hope left. People were so lhorrified when they learned of the largescale

corruption in the land of the brave and free that they stayed in their houses, scared and numbed

.. . I sing that song to let people know that America belongs to everybody who lives there: the blacks,

Chicanos, Indlians, Chinese and the whites…. It’s time that someone took on the reality of the

eighties. I’ll do my best!’

Half a century before, Woody Guthrie had rambled round the country in the fit of a Depression,

writing and commenting on what he saw. The recession of the thirties bit deep, cutting to the heart of

the American Dream.

Guthrie was a nomad, a social commentator, a weaver of fairy tales, a folk poet and a political

activist. His plaintive voice spoke for the oppressed and dispossessed. While the bankers were

evicting entire families, Guthrie wrote this of Pretty Boy Floyd: ‘Well, they say he was an outlaw/But

I never heard of an outlaw driving families from their homes.’ Guthrie was courageous and

outspoken, with ‘This machine kills fascists’ written on his guitar. He realised that songs and words

could be weapons, firing against uncaring governments and ‘legalized crooks’. Songs poured out of

him – ‘Pastures Of Plenty’, ‘Grand ~oulee Dam’, ‘So Long, It’s Been Good To Know Yuh’ – but it was

‘This Land Is Your Land’ that made him public property. Guthrie has been incensed by Irving Berlin’s

jingoistic ‘God Bless America’, and wrote the song as a reply, claiming that America was everyone’s.

At the bottom of the first draft of it he wrote: ‘All you can write is what you see.’

The other influence on Nebraska was another great figure of American popular music, Hank

Williams, the finest artist Country & Western music has yet produced. Williams’ songs conveyed a

feeling of pain and isolation, with titles like ‘I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry’ and ‘I’ll Never Get Out Of

This World Alive’. It is no coincidence that Springsteen chose the title of one of his saddest songs,

‘Mansion On The Hill’, for one of his own songs on Nebraska. Long before the release of the album

he had told Dave Marsh: ‘I love that old country music … I listened to Hank Williams, I went back and

dug up all his first sessions…. That and the first Johnny Cash record.’ (Cash repaid the compliment in

1983 with his Johnny 99 album, which also included a gripping cover of Springsteen’s ‘Highway

Patrolman’, both from Nebraska.)

Ironically, Nebraska was the album John Hammond had envisaged Springsteen making for his CBS

debut ten years before, in the style of Bob Dylan, solo and acoustic. But Springsteen’s background

was not in folk, and the only element of Dylan’s career which had ever impinged on the young Bruce

was his controversial electric years of 1965/6. Springsteen’s adolescence was a diet of British Beat,

R&B, and rock’n’roll. The folk influence had only been apparent on the near-disastrous ‘Mary Queen

Of Arkansas’ from his first album, and the quirky ‘Wild Billy’s Circus Story’ from 1974. Now he

seemed to change direction, in a turnabout that was in the opposite direction to Dylan’s own. Dylan

had horrified the folk purists in 1965 by going electric. In 1982, Springsteen went from rock to

acoustic.

Nebraska had not started as a solo album; it just happened that way. Springsteen had written the

songs in about two months. He then bought a tape recorder so that he could record demos to play to

the band. He told InternationalMusician and Recordin,g World: ‘I got this little cassette recorder that’s

supposed to be really good, plugged it in, turned it on, and the first song I did was “Nebraska”. I just

kinda sat there: you can hear the chair creaking on “Highway Patrolman” in particular. I recorded

them in a couple of days…. I had only four tracks, so I could play the guitar, sing, then I could do two

other things. That was it. I mixed it on this little board, an old beat-up Echoplex.’

The tape was taken to the recording studio and was recorded in filll band versions, but Springsteen

was dissatisfied with the results. The cassette still seemed to sound better. So Springsteen and the

record engineer set about the task of making a master out of the home-made demos.

Initially, the album alienated many of his fans, as evinced by the slow sales, but halfway through

1983- it had sold a million copies in the States, and won a number of critics’ polls.

The album’s critical reception was generally healthy, with many writers surprised by Springsteen’s

honesty in laying his music so openly on the line. The comparisons with Guthrie and Williams are

apparent on the finished album, but there were also echoes of some of the best American rock

writers: the Band’s Robbie Robertson, Randy Newman and Tom Waits. Robertson (ironi-~ cally, a

Canadian) had proved himself a diligent and sympathetic chronicler of American history with songs

like ‘The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down’ and ‘Rocking Chair’, and Newman and Waits had a

penchant for singling out low-life characters on their albums. The eclectic Ry Cooder had also tackled

a project as ambitious as Nebraska with his 1972 album, ‘Into The Purple Valley’, which dwelt on the

Depression era through the songs of Guthrie and Sleepy John Estes.

Like Guthrie’s and Steinbeck’s characters, the people on Nebraska are victims, manipulated by

faceless bureaucrats and political systems which are beyond their comprehension or control. In

conversation with Chet Flippo of Musician Springsteen said that it was about the breakdown in

spiritual values: ‘It was kind of about a spiritual crisis, in which man is left lost. It’s like he has nothing

left to tie him to society anymore. He’s isolated from the government. Isolated from his job. Isolated

from his family. And, in something like “Highway Patrolman”, isolated from his friends.’ It is a record

for America under the Reagan administration. But throughout he observes these victims with

characteristic sympathy, and recognises that their individuality cannot, will not, be crushed.

Knowing the care that Springsteen attaches to his records, the starkness of this, his sixth album, is

symbolic of his desire to convey the topicality and earnestness of the songs. They are hung on the

bare frame of a simple guitar and harmonica, so that the lyrics will be paramount. By now, he was

confident enough in his lyrical abilities and the inherent strength of his characters to let them stand

on their own merits, and Nebraska’s strength lies in that starkness. On those ten tracks, there was

nothing for the singer to hide behind.

The title track is based on the Charlie Starkweather killings in Nebraska in 1959, events which

Terence Malick brilliantly depicted in his 1973 film, Badlands. Starkweather and his girlfriend had

gone on an orgy of killing in the badlands of Wyoming, and Springsteen contacted Ninette Beaver,

who had written a book on the couple, to obtain further background material.

Springsteen’s writing has always had a strong cinematic feel, never more so than on the Nebraska

songs. ‘Atlantic City’, Springsteen’s tale of racketeering on the boardwalk (a bitter distance from the

‘Little Eden’ of ten years before), obviously had some connection with Louis Malle’s 1980 film of the

same name. ‘Highway Patrolman’ refers to the loyalty of friendship so apparent in the films of John

Ford. ‘Mansion On The Hill’ has the atmosphere of a Holywood forties film noir, and the home in

‘My Father’s House’ sounds as if it’s straight out of Psycho! Indeed, so much of the album, starting

with the bleak cover shot, is like watching a black and white film. ‘Johnny 99’ could well have been

played by John Garfield or the sullen young Brando. The congregation on ‘Reason To Believe’ could

well be singing ‘Shall We Gather At The River?’ from any one of a dozen Ford films (and

representing the album’s darker side, the preacher could well be palyed by Robert Mitchum from

Charles Laughton’s eerie Night Of The Hunter).

Springsteen told Rolling Stone in 1978 about the visual aspect of his songs: ‘There’s no settling down,

no fixed action. You pick up on the action, and then at some . . . point . . . the camera pans away, and

whatever happened, that’s what happened. The songs I write, they don’t have particular beginnings,

and they don’t have endings. The camera focuses in and then out.’ A statement which mirrors Jean

Luc Godard’s ‘All my films have a beginning, a middle and an end – but not necessarily in that order!’

That cinematic element in Springsteen’s songs is dictated by the artist, zooming in and out on specific

scenes, a slice of the action. The original cover for Darkness On The Edge Of Town (and which was

subsequently used for the 12-inch single of ‘Rosalita’) was a black and white shot of Springsteen

sitting idly outside a gas station at night, caught in the viewfinder for a brief second, before moving

on. He may paint in big screen Technicolor, but Springsteen crams his songs with incident and detail

to make them intimate.

Also evident on Nebraska is the constant, deferential use of the word ‘sir’. The characters are

resigned to life at the bottom of the ladder, and despite America’s being the great democratic

paradise, there are still class differences. Even facing death (‘Sheriff, when that man pulls the switch

sir …’) all men are not equal. They are the underdogs, the people that the rest of the country (even

their own families) wipe their feet on. Robbed of the dignity of labour, crime becomes their only

option. These are the ‘Dustbowl Ballads of 1982’. ‘Johnny 99’ could well be a petty criminal, or playing

in a rock’n’roll band. But he turns to crime, and in a trial which is a cross between Kafka and Dylan in

‘Drifter’s Escape’, Johnny pours his heart out to ‘Mean John Brown’. But to no avail. As Dylan sang

on his 1968 song: ‘The judge he cast his robe aside, a tear came to his eye/You fail to understand’, he

said, ‘why must you even try?’. ‘Atlantic City’ is a bitter, dark song, but as on all of Springsteen’s best

work, there is a residual strand of hope: ‘Well I guess that everything dies, baby that’s a fact/But

maybe everything that dies someday comes back.’ ‘Highway Patrolman’, one of Springsteen’s finest

songs, has a stately, dignified narrative, which is anguished in its intensity.

Binding the songs is a sense of loyalty, whether it is the loyalty of the killer on the title track to his

girlfriend (a spellbinding opening image with the sense of small-town America, depicting the girl

‘twirling her baton’), or the loyalty of a son to his father, and his inability to atone for childhood sins,

or the loyalty of a man for his brother gone bad. The crisis of duty over filial affection is weighed up,

but the consideration that ‘man who turns his back on his family just ain’t no good’ overcomes the

guilt of turning a blind eye. But buried even deeper than that sense of loyalty, below even

Springsteen’s care and concern for the victims, at the core of the album, lies a sense of dignity, a sense

of optimism and wonder, that ‘at the end of every hard earned day, people find some reason to

believe’.

Springsteen’s characters seem to have come from somewhere, before being captured in the songs.

For one brief, crucial moment, before they drive off, whether it is on the boardwalk, the night time

drive down Kingsley, the wreck on the highway, on the Canadian border or in the mansion on the

hill. And while the country lumbers on past them, towards an unknown destiny, those characters

exist, and have been given a voice.

Glory Days

It had been four years since Springsteen’s last rock’n’roll album and four years is a long time in

rock’n’roll terms. Four years that begged the question: could Bruce Springsteen still pack a punch, or

was he just punching the clock? It was another long wait to the next alburn, and the advance sounds

were not promising. On 10 May 1984 Bruce Springsteen’s first new song in 18 months and his first

rock’n’roll song in all those years, the single ‘Dancing In The Dark’ was released. The opening lines

were ominous: ‘I get up in the evening/And I ain’t got nothing to say . . .’. Some of the lines like ‘I

need a love reaction’, were dire. Moreover, ‘Dancing In The Dark’ was dance-rock, complete with a

synthesiser. It even appeared in three additional special 12-inch dance mixes, supervised by New

York master mixer Arthur Baker, the man who achieved the impossible by putting the funk into

New Order. The new version stretched the original by emphasising the rhythm, but it seemed little

more than a concession to the current fad for alternate mixes. The B-side of all versions, however,

was an interesting rarity, ‘Pink Cadillac’ a Springsteen song which Bette Midler had included in her

live shows for a couple of years. It was a pensive, bluesy ballad in the tradition of ‘Fire’, but it lacked

that song’s brooding sensuality, and frittered away its potential with regurgitated auto imagery and

recycled Biblical references. The single, however, shot up the charts. In the USA it was only kept from

the top spot by Prince’s ‘When Doves Cry’. In the UK it initially only got to nurnber 28, but then,

after a BBC special about Springsteen was screened just before Christmas, it started climbing again,

rising to nurnber 4, eight months after it was releascd.

The real meat, however, was not far behind. Born The USA was released on 4 June in both the UK

and the USA. In the UK it shot straight into the album charts at No.2, showing how well his 1981 tour

had established him, while in the States it made top of the charts in three weeks. Within a few months

it had sold over 5 million copies worldwide. The reviews were glowing, with critics delighted to find

Springsteen back in tandem with the E Street Band, and leaving behind the insularity of Nebraska.

Newsweek welcomed his return as a rock’n’roll hero. Village Voice called it his best album to date.

Rolling Stone proclaimed it ‘a classic’. The Los Angeles Times’ Robert Hilburn (a long-time fan)

waxed Iyrical: ‘John Lennon was wrong when he said no-one has ever improved on the pure rock

rejoicing of Jerry Lee Lewis’ “VVhole Lot Of Shakin’ Going On”. In terms of sheer exhilaration, Bruce

Springsteen’s “Born To Run” in 1975 blew “Shakin”‘ away. Nine years and four albums after “Born To

Run”, Springsteen continues to blow ’em away!’ In Britain, Adam Sweeting of MelodyMaker had his

finger on the pulse when he wrote: ‘With successive releases, Springsteen’s version of “rock” has

moved further and further from any remaining vestiges of what it might feel like to be a delinquent,

under-age beer drinker…. Despite the familiarity of themes and forms, Born In The USA makes a

stand in the teeth of history and stirs a few unfashionable emotions.’

The actual release of Born In The USA was characteristically fraught. Since The River in 1980,

Springsteen had stockpiled around 100 songs. Often the band had gone into the studio and recorded

numbers so new to them that they did not know the chords. In order to keep it fresh there was very

little rehearsing. These tracks ranged from rough demos, the most immediate of which became

Nebraska, to finished full band songs, which became the core of Born In The USA. Those songs were

endlessly sifted through until the final dozen tracks were selected – ironically, the album’s anthem,

‘No Surrender’, was only included at the very last minute, as a tribute to Miarni Steve, who had

decided to leave the band.

The second single lifted from Born In The USA was ‘Cover Me’, which included a bonus on the B-side

– a live version of Tom Waits’ haunting ‘Jersey Girl’, from his Heart Attack And Vine album. Many

people felt the song was written for Springsteen, but Waits actually wrote it for his wife, a real Jersey

girl. Springsteen had included it in his live shows, and duetted with Waits on the song in Los Angeles

in 1981.

Since the release of Nebraska in 1982, Springsteen’s activities had kept him confined to the studio,

recording again with his band. He did return to impromptu live work, though, averaging one

appearance a week at various Asbury clubs and bars (including one appearance at an Italian joketelling

contest, where he failed to win the $25 prize!). The bands he jammed with were old favourites,

such as Cats On A Smooth Surface, joining them onstage at the Stone Pony in Asbury Park for a

version of ZZ Top’s ‘I’m Bad, I’m Nationwide’. He also appeared regularly with Clarence Clemons,

and with Bystander he premiered ‘Dancing In The Dark’ at Asbury’s Gl~ub Xanadu in May 1984.

Four of Springsteen’s songs—’It’s Hard To Be A Saint In The City’, ‘Adam Raised A Cain’, ‘She’s

The.One’ and ‘Streets Of Fire’ – were used effectively at this time in John Sayles’ film Baby It’s rOu,

which included a scenic detour in Asbury Park.

Such relative inactivity from Springsteen allowed the E Street Band to pursue their own activities.

Max Weinberg finished and published his book on the great rock drurnmers, The Big Beat, early in

1984. Clarence Clemons set up a new band, the Red Bank Rockers, who released their debt album on

CBS in late 1983. They attracted great notices for their live appearances, but when the music was

captured on vinyl, it lost its spontaneity, and sounded forced and desultory. Miarni Steve persevered

with his own band, the Disciples of Soul, but while Clemons also continued with the E Street Band,

Miami Steve decided to go it alone in early 1984. Springsteen noted the move on ‘No Surrender’, and

it is remembered in ‘Bobby Jean’. The split was amicable; as Van Zandt said: ‘We were friends long

before we played together, we’ll be friends forever,’ and on the inner sleeve of Born In The USA

Springsteen bade Little Steven ‘a good voyage, my brother’, in Italian. Any doubts which may have

lingered about the mood of their parting were scotched on 20 August 1984 when Miami Steve joined

Bruce on stage at the Meadowlands Arena in New Jersey for a classic version of Dobie Grey’s ‘Drift

Away’ and a scorching ‘Two Hearts’. Little Steven’s second album, Voice Of America, was released at

the same time as his former boss’s, and picked up sympathetic and occasionally glowing reviews,

with critics singling out its overtly human rights sentiments.

Although he had not joined the E Street Band officially until 1975, Steve Van Zandt had been a longtime

companion, having been a member of Steel Mill. With such a gap in the ranks, someone very

special was required to join as second guitarist. The person chosen was Nils Lofgren, who joined the

band, avowedly for a year starting with their 1984 US tour – after borrowing a boxful of bootlegs and

live tapes to acquaint himself fillly with his new band’s style. He and Springsteen had first met in 1969

when they both shared an audition for the Fillmore West, and their paths had crossed several times

over the intervening years. Lofgren was a gritty rock’n’roller of the old school, who started life as a

precocious 16-year-old guitarist in Chicago before talking his way into Neil Young’s backing band

and contributing to Young’s classic 1970 albumAffer The Goldrush. With his own band, Grin, Lofgren

then established a devoted cult following. He is also a songwriter, his style veering from the punchy

‘I Came To Dance’ to the sublime balladry of ‘Shine Silently’. His interpretation of the Goffin/King

standard ‘Goin’ Back’ emphasised his appreciation of rock history, which must have rated with

Springsteen. Following his reunion with Young on the latter’s 1983 ‘Trans’ tour, Lofgren played with

Springsteen in Asbury Park the Christmas of that year. Springsteen reckoned he had the same

musical feelings as Van Zandt: ‘We looked at music in the same way and cared about the same

things.’

With his band in order, a new album under his belt, even Springsteen could no longer ignore the

video boom. After discussions with video aces Godley and Creme, Springsteen eventually chose

director Brian de Palma (Phantom Of The Paradise, Carrie) to shoot him in his first video

performance for ‘Dancing In The Dark’ in June 1984. His only previous promotion video had been

for ‘Atlantic City’ in 1982, but he did not feature in it. The video showed only views of the town shot

from a moving car. He remained opposed in principle to videos, as he believed that his songs were

already full of cinematic detail and that visuals introduced an extraneous element. He also feels that

the songs work on people’s imaginations and that it is up to each individual to see what the song

suggests to him, and not to have someone else’s vision imposed on him. Nevertheless, he gave way

for ‘Dancing In The Dark’, and was to appreciate that this gave him an audience in pre-teen kids.

Moreover, he regarded the video as sufficiently successfill to commission John Sayles to shoot

another performance video for the ‘Born In The USA’ single, but the finished product was criticised as

Springsteen was clearly miming on it.

Any rumours that this burst of activity was to be Springsteen’s swansong were scotched on 29 June

1984, in St Paul, Minnesota, when Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band kicked offtheir first tour in

three years with a marathon three-and-a-half-hour,30-song set. Springsteen proved he had coped

with the intervening years, and did not compromise a jot in those shows. He had straightened up his

diet, kicking his junk food habit, and having chefs prepare large bowls of vegetables for him as soon

as he came offstage. He also pumped iron at local health clubs on the road, and the whole band

regularly worked out. Raring to get back on the road, Springsteen was fitter, healthier than ever, as

he told Debby Miller: ‘Jump up and down and screarn at the top of your lungs for 20 rninutes and see

howyou feel!’

The demand to see Springsteen in concert had not abated during his three-year lavoff. In New Jersey

the 200,000 tickets for his Meadowlands shows were sold out in one day! In Wisconsin, such was the

demand for tickets that 13 July was declared ‘Bruce Springsteen Day’ by Govemor Tony Earl.

The ’84 tour included full band versions of the solo songs Springsteen recorded for Nebraska – the

title track, ‘Atlantic City’, ‘Mansion On The Hill’, ‘Used Cars’ and ‘Highway Patrolman’, all of which

grew in stature when augrnented by the discreet band backing. From Born In The USA, ‘No

Surrender’, ‘Glory Days’ and ‘Working On The Highway’ became integral parts of the set. The

evening wrapped up with a swaggering version of the Rolling Stones’ 1968 ‘Street Fighting Man’,

which Springsteen included because, as he told friends, he just had to sing the line: ‘So what can a

poor boy dorcept sing for a rock’n’roll band.’ Also included were perennial live favourites like ‘Born

To Run’, ‘Fire’, ‘Thunder Road’, ‘Rosalita’ and ‘Badlands’. He adeptly juggled around all facets of his

recorded career, 1982’s ‘Used Cars’, for example, segued beautifi~lly into 1984’s ‘My Hometown’; the

gloomy ‘Downbound Train’ from Born In The U5A led into the sombre ‘Atlantic City’ from

Nebraska. Even the sluggish ‘Pink Cadillac’ came to life in concert, particularly with such laconic

Springsteen intros as: ‘It seems, according to the Bible, way back when, Eve showed Adarn the apple,

and Adarn took a bite. There’s gotta be more to it than that. Fruit?’

As well as ‘new boy Nils Lofgren, Springsteen featured anothe new E Streeter, back-up singer Patti

Scialfa, who had worked witl Southside Johnny, and whom Springsteen had seen singing in al

Asbury bar, where he was enchanted by the ‘country feeling’ in he voice. The presence of newcomers

did not dampen down th spirit of the band on stage: on Halloween Night, which found th E

Street Band at the Los Angeles Sports Arena, Springsteen cele brated the date with a suitably hammy

intro. He made his entranc Iying on a coffin, impervious to the attempts by Clarence Clemon and

Patti Scialfa to bring him back to life, until he was given hi guitar. Then he was off, bursting into a

frantic version of Jerry Le Lewis’ ‘High School Confidential’. But there was also a mor muted facet to

the concerts. At the Takoma Dome in Washingto] DC on 19 October, for the first time in 11 years he

did not pla ‘Rosalita’. Instead he took at some shows to finishing with th relatively more subdued

‘Racing In The Street’, highlighting th darker side of his recent albums.

In keeping with his desire to take his music to his real fans, Springsteen’s ’84 tour reached many

places usually ignored by touring bands, including a notable detour to Lincoln, Nebraska. In all the

tour was to last 14 months, and was not only to criss-cross the United States, but was to take him for

the first time to Australia and the Far East. The Jacksons’ ‘Victory’ tour was launched at the same

time as Springsteen’s and, although a huge commercial success, suffered notably by comparison.

There was howls of protest at a charge of $30 a ticket, plus a minimum ordel of four, and Bruce

would play for nearly three times as long Critics remained unimpressed by the Jacksons’

technological spec tacle, but were swayed by the earthy rock’n’roll power of Springsteen’s shows.

Typical was the comment at the end of the review in the venerable New York Times: ‘What makes

Mr Springsteen such a satisf ying harbinger of “the rock and roll f uture” is not his anticipation of

todays trends … but his role as a musician working lovingly within the rock tradition to make serious

adult art. That’s worth cheering about, just as much as the spellbinding fervour of his actual

performances.’ After three years away, he had returned to the spotlight, and with shows infused

with vigour and integrity rightly reclaimed his crown as rock music’s greatest live performer The

coronation itself was to come later when he was chosen by Rolling Stone readers as the Artist of the

Year. Although it was the fourth time in six years he had won this accolade, he also scooped five

other awards: Album of the Year, Single of the Year (‘Dancin~ in the Dark’), Male Vocalist,

Songwriter, and, with the E Street Band, Band of the Year. Only in 1980, when he released The River.

had he amassed such a total. Clearly for lovers of rock, the tour and the new album were the events

of the year.

Significantly, Born In The USA was credited only to ‘Bruce Springsteen’, with no mention of the E

Street Band on the label o cover. And that cover! Three years for a shot of Bruce Spring steen’s bum!

One London paper even speculated that the caF hanging out of his back pocket was a none too subtle

gay hallmark.

The inner sleeve included ‘Thanks’ to scriptwriter/director Pau Schrader (Taxi Driver, Blue Collar,

American Gigolo). ‘Thank~ always’ to John Hammond Sr who helped bring the wheel full circle: the

man who had brought Bruce Springsteen to the world decade before, and who proved his ears were

as acute as ever with his signing and production of the raw Texas blues of Stevie Ray Vaughan in

1983.

The sound of Born In Thc USA is wholeheartedly, emphatically rock’n’roll – from the classic

Springsteen ‘Sha-la-laing’ of ‘Darlington County’ to the Creedence-style chooglin’ of ‘Working On

The Highway’. It also sounds surprisingly un-E Street – there is precious little saxophone, the whole

band sounds mixed down, the keyboards are sparsely used, – and the record marks the debut of

synthesisers on a Springsteen album. The overall impression is of Max’s drums driving the songs

along, relentlessly propelling them with a force few in rock can match. It is steeped in traditional rock

references and influences, and while there are concessions to metronomic pop on songs like ‘Dancing

In The Dark’ and ‘Cover Me’, Springsteen flouts the current fashions with rock music of such force.

The album marks a further development; play it back to back with Born To Run and you are aware

of the differences – the Iyrical sparseness of the later record, the hardhat impact of the songs and their

production, the authenticity of the characters and their situations. Born To Run is larger than life,

Born In The USA presents experience at life-size.

Born In The USA is a concept album (although we all breathed a sigh of relief when we thought we’d

seen the back of those mutants!). It is a series of songs f~om a man about to turn 36, trying to come

to terms with his age and his vocation in what is, prunarily, a young man’s game. Four of these

songs – ‘Born In The USA’, ‘Working On The Highway, ‘Downbound Train’ and ‘No Surrender’ are

crucial. They chart the dissipation of idealism, the futility of clinging to what has gone, the exultation

of love and partnership, and the acceptance of maturity in the face of diehard teenage dreams. Tlley

are, essentially, rock’n’roll dilemmas, which Springsteen tackles head on, because he has lived them,

because he is living them. As a background to these themes, Springsteen draws on the rich legacy of

American popular music – the plaintive hillbilly blues of Jimmie Rodgers on ‘Downbound Train’, the

Creedence-based, Eddie Cochran iock of ‘Working On The Highway, the Spectorish fusion of ‘No

Surrender’, the sly disco rhythms of ‘Dancing In The Dark’. He even starts pillaging his own past on

the album – ‘Darlington Country resembles the ‘up’ songs on The River. The stately drums which roll

in the title track, the first lines of the song, take us straight to the heart of darkness: ‘Born down in a

dead man’s town/First kick I took was when I hit the ground’ – Ground down and ensnared from

the very moment of birth. It is a sombre homage to Chuck Berry’s ‘Back In The USA’, the song which

eulogised and esteemed the values which Springsteen finds corrupted. Being away, Berry misses the

skyscrapers, long highways, drive-ins and corner cafes. Chuck’s back from exile, he’s missed the

hamburgers that ‘sizzle on an open grill night and day’ and fondly recalls ‘the juke box jumping with

records’. These are the things that Springsteen would miss, too. But while Berry’s 1959 song ends

with the triumphant testimonial: ‘Anything you want, they got right here in the USA,’ all Springsteen

finds a quarter of a century on is that ‘there’s nowhere to run, ain’t nowhere to go’. The chil&ood

belief in the American Dream has dissipated; it ends in disillusion and grief.

The title song traces a person’s life from birth to his mid-thirties. During his adolescence Springsteen

watched the country torn asunder by Vietnam, and his sympathy with the plight of the Vietnarn

Vets is such that ‘Racing In The Street’ was inspired by Vet Ron Kovic’s book Born On The 4th Of

July, and he has played a number of Vet benefits. In ‘Born In The USA’, after the ‘hometown jam’ of

the second verse, the intransigent youth is sent off’to a foreign land to go and kill and yellow man’.

The earlier ‘Highway Patrolman’ dealt with a similar situation, shipping the brother of the song’s

narrator to Vietnam in ’65. ‘Born In The USA’ also has two brothers, but both brothers are serving

there, now. Moreover the older brother dies at Khe Sahn, the Iynchpin of the 1968 Tet Offensive,

which proved, indisputably, that America could never win that war. ‘They’re still there, he’s all gone.’

And nothing changes, save the finality of one man’s death, and its repercussions. On his return home

the song’s narrator is a spent force – no hero, just an embarrassment. This helps explain the sleeve

credit to Paul Schrader, whose Taxi Dnver, ends with the protagonist, Travis Bickle, shooting into a

crowd, his revenge as a Vietnam veteran on a society that has spurned him. Back home, ‘the shadow

of the penitentiary’ nestles next to ‘the gas fires of the refinery’. The alternative to death in VietNam

is itself pretty bleak. Now, if you’re ‘Born In The USA’, there is none of the climactic optimism of

‘Thunder Road’ or ‘Wreck On The Highway’. Now ‘I’m 10 years running down the road/Nowhere

to run, ain’t nowhere to go.’

‘Working On The Highway’ is roots rockabilly, slapped bass and jagged guitar. The musical feel is

steeped in the fifties, although the lyrics go back to the thirties, to the era of Jimmie Rodgers, ‘The

Singing Brakeman’, flashing by Paul Muni as a fugitive from a chain gang. The London Guardian

called it ‘the best prison rocker since “Jailhouse Rock”.’ In the song’s trial, ‘the prosecutor kept the

promise … the judge got mad’ recalls the courtroom hysteria of ‘Johnny 99’. Despite its exuberant

musical punch, the feel of the song is confined, trapped again, whether it’s the boredom of working

on the two lane blacktop at the beginning, or the confinement of life on the Charlotte Country Road

Gang at the end.

‘Downbound Train’ is the first opportunity to draw breath on the album, a brooding, pensive ballad,

bleak and uncompromising. A splintered marriage opens the song, a resigned ‘we had it once, we

ain’t got it anymore’. The motif of the railroad runs throughout the song. Springsteen includes a

Nebraska-ish tip of the stetson to Hank Williams’ tune ‘I Heard That Lonesome Whistle’, and

embraces a tradition which stretches through ‘Waiting On A Train’, ‘Love In Vain’ and ‘Mystery

Train’ – C&W, blues and rock, the grand triumvirate of American popular music. But in the eighties

the trains aren’t running anymore, and nobody’s riding boxcars. There is a sense of emptiness,

enforced by the run through the woods at the song’s conclusion. In the big, cold house stands an

empty bridal bed, which recalls the sense of chilling isolation evoked by ‘My Father’s House’. A

sombre mansion on the hill, once a place of happy, shared memories, it now stands empty and silent.

‘No Surrender’ is the album’s clarion call, with a chorus addressed to the fans: ‘Like soldiers in the

winter’s night with a vow to defend/No retreat, no surrender!’ It is Springsteen’s statement of intent

and faith, to stay true to the power and the glory of rock’n’roll. He is celebrating the rock’n’roll of

which Chuck Berry claimed on ‘Schooldays’ in 1957, ‘We learned more from a threeminute record

than we ever learned in school’. But by the last verse of ‘No Surrender’, there’s a weary resignation

to the inevitability of ageing, something to which you have to surrender. The idealism of the first

verse is tarnished in the second, and has gone in the third. Springsteen accepts that the baton has

been passed on to a new generation. In lines which deliberately invite comparison with Bob Dylan’s

idealism of 1963: ‘There’s a battle outside and it’s ragin’/ It’ll soon shake your windows and rattle

your walls/For the times they are a-changin’.’ By 1984 the times have a-changed: Bob Dylan is a 43-

year-old conservative evangelist, and Bruce Springsteen (whom many deemed Dylan’s successor) is

acknowledging: ‘There’s a war outside still raging/You say it ain’t ours anymore to win.’ ‘No

Surrender’ ends with – for Springsteen – the crucial line, ‘these romantic dreams in my head’. The

dreams are not to be poured into any idealised Spanish Johnny or Johnny 99. They are there, but

confined to his head, a reaction to what he has witnessed and experienced, but locked away, and only

to be savoured alone, like a childhood diary, or a three-minute single bought in adolescence.

The whole last verse conveys, perhaps more successfillly than any other song on the album,

Springsteen’s realisation and recognition of his position: ‘I want to sleep beneath peaceful skies in my

lover’s bed, with a wide open country in my eyes, and these romantic dreams in my head.’ The

feeling in those lines again evokes the West of John Ford, of domestic contentment in the face of

adversity, of idealism contained. Of a whole vast country out there, and all you can do is stand and

stare out of your window and contemplate a fraction of that vastness.

The strength of these four songs is that the characters are given a substance and personality, which

stops them being mere ciphers. They are drawn from real life and are sympathetically drawn,

characters who share the same experiences and environment as Springsteen’s audience, with whom

they strike a responsive chord.

It is that substance which renders other songs on the album like ‘Cover Me’, ‘Bobby Jean’ and ‘I’m

Going Down’ ineffectual. ‘Cover Me’ is a throwaway, a disco concession, the sort of song Springsteen

could write in his sleep, but which he usually has the good sense to farm out to others. When he tries

to bolster the song with the lines ‘Times are tough now/Just getting tougher,’ they come across as

merely a sap to the prevalent political/economic climate, especially when the writer’s only solution to

these hard times is to find ‘a lover who will come in and cover me’, which .mply enforces the

stereotype of Springsteen as a male chauvinist nd ersatz romantic.

Despite its inspiration, ‘Bobby Jean’ is Springsteen productionline ‘remember when …?’ Because he

tries too hard, he fails to achieve the wistfillness the song needs. While a line like ‘We liked the same

music, we liked the same bands, we liked the same clothes’ is effective – because those things are so

important to teenagers – to hear a 35-year-old Springsteen sing ‘Now there ain’t nobody, nowhere,

nohow ever gonna understand me the way you did’ is merely embarrassing. It is an embarrassment

repeated by the trite lyrics of ‘I’m Going Down’, an otherwise reliable rocker (despite its beguiling

Tex-Mex intro). Beside other songs on the album which are amongst Springsteen’s most deliberate,

most consumately crafted songs, these come across as weak and clumsy.

However, as well as the four major songs, others songs like the stark and chillingly simple ‘I’m On

Fire’ have great force. It consists of three stabbing verses, pounded by the honed-down chorus. The

almost paedophiliac opening lines are sinister (‘Hey little girl is your daddy home? Did he go away

and leave you all alone? I got a bad desire!’) The all-consuming lust and passion is played out against

a slyly simple beat which fits the pathological lyrics like a glove. Springsteen imagines a knife ‘edgy

and dull’ cutting ‘a six inch valley through the middle of my soul’. It continues with the paranoid ~At

night I wake up with the sheets soaking wet and a freight train running through the middle of my

head’ – it’s as if someone gave Norman Bates in Psycho a guitar! There are no histrionics, no lyrical

legerdemain. As on ‘Factory’ or ‘Wreck On The Highway’, it is Springsteen’s very restraint which

elevates the song, the acts as a powerful argument against those who constantly accuse him of

bombast.

Other songs support the main theme of growing older and disillusioned. With ‘Glory Days’, the initial

impression is that Springsteen has succumbed to the unabashed nostalgia he is constantly accused of,

but by the time the song has wound its way through three laconic verses, the overall mood is of

resignation. The first verse conjures an image of Springsteen sitting down in a bar, revelling in

reminiscences over a beer. The baseball hero sounds initially like the hopeful symbol of Joe Di

Maggio which Paul Simon drew on ‘Mrs Robinson’. But in Springsteen’s son you soon realise that all

this guy has to keep him going are his memories. In the second verse (and the second broken

marriage on the album) there’s a wry acceptance of what has been, as tears give way to laughter, but

by then it’s too late to recapture any of it. By the end of the song, Springsteen himself hopes that

when the times comes, he won’t be sitting round trying to recapture what has been: ‘Just sitting back,

trying to recapture/A little of the glory, but time slips away/And leaves you with nothing, mister,

but boring stories of glory days.’

That those stories could be boring is a revolutionary idea coming from Springsteen. Even by his own

standards, he has championed those whose own ‘glory days’ have long since gone – Gary Bonds,